David Thorold , Curator of Collections (Pre Historic to Medieval), St Albans Museums, discusses how Verulamium developed from the base of an Iron Age chieftain to become an extensive Roman city, before fading away and being eclipsed by St Albans, following the Roman withdrawal.

An Iron Age industrial centre …

The Roman city of Verulamium developed out of a pre-existing settlement; the Iron Age population were farmers, growing crops and keeping some cattle over much of the landscape. These farmers tended to live in non-nucleated settlements often towards the upper slopes of the shallow hills in the area, such as at Prae Wood, Gorhambury and around Folly Lane.

But in the years before the Roman arrival the area around what becomes Verulamium in the valley bottom appears to have become an industrial centre of some kind, alongside a large enclosed area (where St Michaels Church now sits) that may have been the ‘palace’ of the local chieftain.

… becomes a hub for trading with the Romans

This early development may be tied to the raids by Julius Caesar in 55 & 54BC and the resulting settlement that saw the local Catuvellauni tribe becoming favoured trading partners with Rome. Iron ore was being traded out of the region from Cow Roast and Braughing in particular and crossing points in the local rivers would have been of greater importance. The original British name of the area – Verlamion, or Place by the Marsh – seems to confirm that the river Ver would have been shallow enough for a crossing point, making the area a key point in the region where people would pass through and perhaps encouraging development.

The site of Verulamium today (St Albans Museum +Gallery)

The first Town in the Roman period was a small settlement of around 60 acres centred very much on the crossing of the river, with a southwest-northeast trackway running to the north of what is now the church (approximately where Bluehouse Hill lies) and respecting the existing chieftains palace. The main Roman development that we know of is the first rectangular strip houses being laid out to the north of this in what would become Insula XIV.

Initially, Roman development seems to be limited, possibly as we still know little of this period but also quite likely because of the political ties that the Romans appeared to have with the local tribe and its ruler, meaning that flattening of this Town and its structures would have had damaged relationships at a time when the Romans could not afford to lose local support.

A pro-Roman collaborator …

Who the local ruler is cannot be confirmed, but the wealthy burial on Folly Lane dating to around AD 55 points to this individual being the ruler in the period of transition from chieftain to Roman rule. Cassius Dio tells us that while two of Cunobelin’s sons fought the Roman invasion, a third, who had been deposed by his brothers, fled to Rome.

This third brother was Adminius and he may have aided the Romans campaign by persuading the local tribe to throw in their lot with the Romans in return for being restored to the position of King. The Romans were happy to install such local independent rulers on the understanding that their territory would fall under the control of the Roman Empire upon their death, and if Adminius operated as a local client king until his death, then this is another reason for the early Town remaining largely Iron Age in its design and layout.

One interesting element of the character of the early Town was its lack of a permanent Roman military presence; although it was once thought that a Roman fort was placed here, the evidence is now against this. It seems that the local populace was supportive enough for the Romans to feel secure without the need for a large presence of troops in the region.

… and an anti-Roman rebel

Such a policy proved mistaken in light of the Boudiccan revolt in AD 60/61. Although there is no evidence for mass deaths at Verulamium (unlike Colchester or London) – the population having no doubt seen the writing on the wall and fled into the countryside – the first wooden Town of Verulamium was largely destroyed as far as can be ascertained, although in relative terms, there was probably not that much of a Town for Boudicca to burn. Certainly within a year or two, it was trading with London again, as the recently recovered writing tablet from London shows.

Rebuilding the town on Roman lines

With the local client king dying and the early Town’s destruction at the hands of Boudicca occurring close together, the opportunity was now available for a more Romanised Town. Certainly, the new Town features regular roads and recognisable insula blocks appear, while a boundary is marked by a ditch. Watling Street is also laid out around this time, and but the ditches that typically flank it are absent once it reaches what becomes Insula III of the Town.

Although development did not yet stretch out this far on the southern side of the Town, it was clearly intended that that it would eventually do so, and the architectural problems caused by building structures over infilled ditches were clearly being considered. Interestingly, the ditched section of Watling Street does penetrate through the boundary ditch so either Watling Street was built before the boundary ditch, or the outer perimeter of the Town was not intended to hold major architectural structures.

Some elements of the Town’s layout were already fixed however. The orientation of the grid plan was probably determined by the early road crossing the Ver from southwest to northeast and the chieftain’s palace alongside it. As a result, Watling Street approaches the Town from London on an angle, whereas it leaves the Town to the north on a road that fits into the street grid layout. On the south, where the Town’s development was already fixed, it cuts through insula blocks until it links with an existing road (street 12) and then has to dog leg around the Basilica block / chieftain’s palace before aligning itself with the main road heading towards Chester.

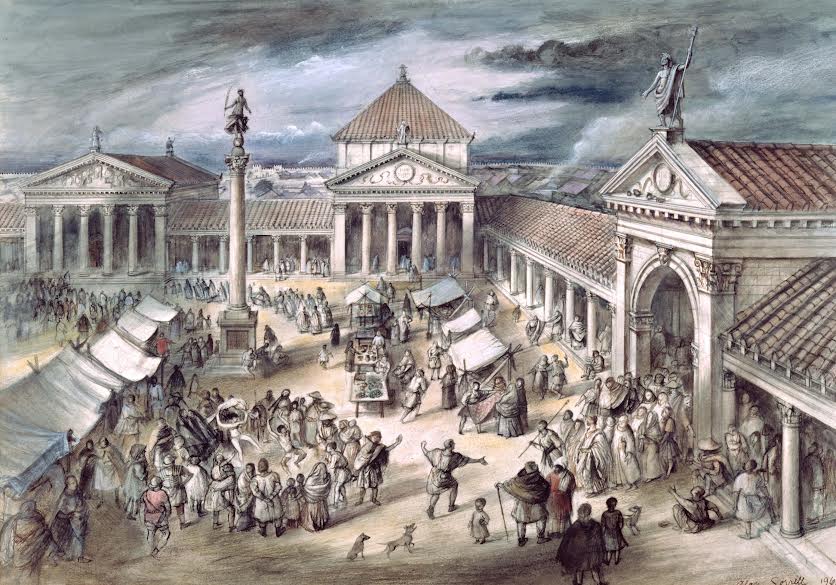

The Basilica and Forum

The forum and Basilica inscription now in the museum dates to around AD 79. Although there has been little excavation on the site since the early twentieth century, it seems likely that this belongs to the complex built on the site of the chieftain’s Palace after the Boudiccan revolt, during the phase of building across the country instigated by Agricola (the inscription was not recovered from excavation so its context is unclear).

The forum courtyard measured 88x98m with two centrally placed entrances (the southern one aligning with the route of Watling Street). The walls were dressed blocks of barnack stone with an internal colonnade supported by columns of segmental tiles faced with white plaster. On the south western side was a building designed either as a temple or curia (council building).

The Basilica was 45m wide and 120m long and had a row of rooms along its NE side, split by two entrances onto Watling street. The Basilica and Forum complex would have been very imposing, with the Basilica being the largest structure in the region.

Artists reconstruction of the Roman Forum at Verulamium (St Albans Museum + Gallery)

Following its rebuild, Verulamium grew quickly. The Bath House complex was added in the early second century as was the Theatre, while the Town seems to have expanded further than even the Romans had planned – sections of the boundary ditch were being built over by the time the baths and theatre were being constructed.

The Roman Town was built largely of timber. Evidence suggests that it featured simple rectangular buildings of 1 or 2 stories centred around Watling St and the southwest to northeast road that crossed the river Ver. The buildings were timber framed with wattle and daub walls, plastered white and chalk, clay or wood plank floors. Most were no doubt shops of the strip design, built to have an entrance fronting on to the road displaying the wares of the owners, with more produce inside and the upper floor reserved for storage and the family home. Verulamium seems to have quickly developed as a town of shops in this way, serving the needs of the soldiers and traders who frequented the road.

Building construction, Verulamium (St Albans Museum + Gallery)

Over time, a range of secondary industries would also have sprung up. Chief amongst the new urban trade and craftsmen was no doubt the carpenter, whose abilities would have been called on to build and maintain the Town. Likewise, the skills of the plasterer would have been needed. Many other professions also sprang up within the Town. There is much evidence for smithing of metals and from this early phase, no doubt linked with the ongoing trade in iron ore. Some of the new professions were small in scale – weavers, needle makers and the like could all work from home, and many of the objects found all clearly attest to the continued importance of agriculture and the countryside to the new professions of the town – butchers, bakers, weavers and many toolmakers were all making produce that came from the land, and Verulamium’s primary function was probably that of a market town where agricultural produce could be traded.

Nonetheless, Verulamium also developed urban professions that relied more upon the new trade routes that the Romans opened up. In the first and second centuries, a number of pottery business were set up making use of local clay to produce pottery, amphora and mortaria that were sold locally at markets and also exported elsewhere. The new urban centre would in time allow for specialised craftsmen such as fullers, cobblers, potters, tilemakers, leatherworkers, teachers and doctors to name but a few.

A devastating fire that damaged small businesses

All of this growth came to a sudden end around AD 155 when the town burnt down for a second time. Unlike the Boudiccan intervention, this appears to have been a wholly accidental fire – the town had a large number of smiths operating within it and the buildings were largely built of wood, and many small localised fires are known – this one seems to have caused almost total devastation, with much of the town destroyed (only that area south of the triangular temple appears to have survived relatively unscathed. With such devastation, it is not surprising that the town took some time to recover. The forum and Basilica were amongst the first major structures to be rebuilt, but the (relatively new) bath complex was not rebuilt for many years.

While occupation no doubt resumed almost immediately, many sites appear to have been left empty for some time, and the nature of the town appears to change. It had earlier been a market town with a number of industrial trades, especially metalworking taking place within it. After the fire, Verulamium displays a large number of opulent townhouses, with evidence for industrial activity much reduced.

The small business class that had been developing at Verulamium seem to have been largely wiped out financially by the economic effects of the fire (at least in terms of what the archaeological record shows) and being unable to restore their former shops and homes were instead hired by the richer elite who were more able to ride out the loss of their Town properties and rebuild.

Opulent new town houses

Although many of these new grand Townhouses have several rooms, it was common Roman practice to hire out rooms to individuals or businesses, so it unlikely that any one house was used simply by one family. It may be that the smaller businesses continued to operate from these premises, paying rent to the house owners, or that smaller shops in the style of the earlier period remain to be found in the less central areas of the Town not yet excavated.

Certainly there must have been homes for the less well off, who lived within the Town but would not have been able to rent let alone own one of the major Townhouses that were built. Nonetheless it is these Townhouses that really symbolise the later Town of Verulamium after the second century fire. Most of these Townhouses appear to have been built across Insulae IV, XXIV and probably XXI, providing a suburban area of wealth away from the hustle and bustle of the Town centre and Watling Street.

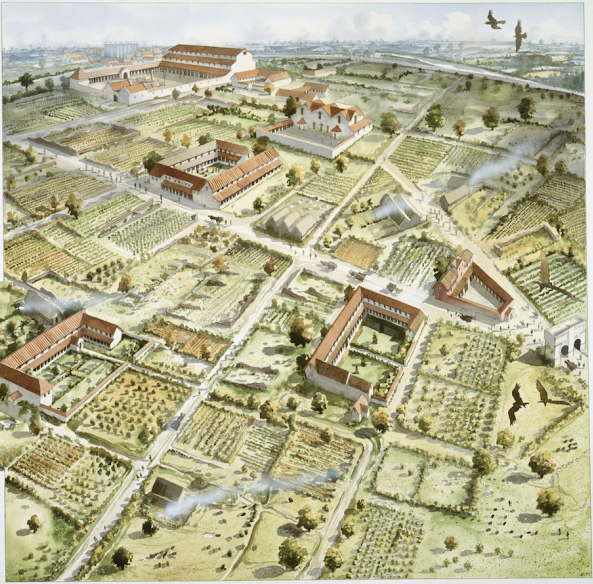

The villas of Verulamium (St Albans Museum + Gallery)

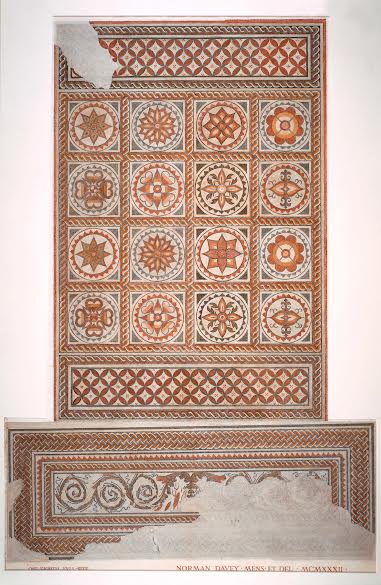

The best excavated of these townhouses is building 8 from Insula IV, part of which is on display in the park today. This was in plan a rectangular strip with a projecting wing on each end, built out of brick. The southern wing, the best preserved part of the structure as it was terraced into the valley slope, included three rooms that contained mosaics, and a number of other tessellated floors.

Two of the rooms with mosaics were also heated with a hypocaust system that ran under the floor and up into the walls before the hot air percolated out through the upper floor’s roof. The northern wing was probably the kitchen and may have included servant’s quarters, while the joining strip had a number of smaller rooms, a long linking corridor and the stairs to the upper floor.

Mosaic floor from a villa in Verulamium (St Albans Museum + Gallery)

Excavation, aerial photography and geophysical analysis suggest that there are around 6-8 such houses in each of these insulae (although they may not all be contemporary with each other) and they all feature similar quality mosaics, decorated wall plaster, and architectural features. There are a number of other Townhouses in some of the other insulae too. Clearly there was a wealthy elite who were living in the Town. This would have been standard practice in the Roman empire but the Britons were slow to adopt – evidence shows that the aristocratic elite initially remained living on their farmsteads/villas. It is only after the fire of AD 155 that wealthy Townhouses appear which could provide an alternative home (or a seasonal residence) for this group, so it seems that it took a few generations for the elite to adopt this element of Romanisation.

The Roman walls

One of the last major events in the history of the Town is the construction of the Town Walls. These come quite late – around AD 275 – and it is worth noting that while the Town always had some form of boundary prior to this. The mid first century ditch that runs around the southern, western and northern sides of the Town was probably a legal/social barrier (and may also have kept cattle out) The timber bank that runs on the eastern side of the Town from the very beginning appears to be more concerned with preventing flooding from the river it runs alongside. There is also the question of the Fosse – a bank and ditch (now eroded flat and filled in respectively) that protrudes beyond the western edge of the Town later marked by the Town wall. Dating evidence for this remains thin, but there is some evidence to suggest that this formed part of a new Town perimeter constructed somewhere around the middle of the second century that also included the still very deep section of ditch visible just beyond the London Gate, forming a boundary that on the south and west sides of the Town extended slightly beyond the later limits of the Town Wall.

The Town wall itself lacks a true military design – it encompasses an area of land far larger than appears necessary, including a large perimeter that lacks substantial building, it gives the high land away to anyone outside the wall on the south western side, and it largely lacks defensive towers and bastions. Instead the wall appears to be for civic pride, with perhaps an element of control regarding access (for taxation of merchants from London perhaps) and a defensive quality regarding dangerous, but less disciplined enemies than armies – cattle raiders for instance. It is worth pointing out that the highest section of the wall, and the one that includes most of the towers, is that which the traveller from London faced when they approached the city. In contrast, when they passed out of the Town on the north west through the Chester Gate, the wall was smaller and featured no turrets! In keeping with the largely planned nature of the Town, most of the gateways were built some time before the wall itself.

There is one further area of the Town to be discussed – the perimeter. When the Town ditch was laid out around AD 155 this enclosed an area larger than the urban nucleus of the Town, with a less built up perimeter also enclosed. The Town seems to have spread quickly into this perimeter and even over the ditch quite soon. When we look at the Town enclosed by the wall, it also has a less built up perimeter area surrounding the urban core. This may have been for less urban activities – crops may have been grown, or cattle corralled within the Town walls at night, or the Town’s grain may have been stored in granaries in this zone. Recent work using geophysical analysis also suggests that areas in this perimeter might have been given over to specific activities, such as those mentioned above, or to more industrial ones, perhaps to help limit or contain dangers such as the second century fire.

The protracted decline of Verulamium

The Town’s general layout does not change in the fourth century, although the theatre is abandoned and is used as a general rubbish dump, otherwise Town life continues through the fourth and into the fifth century. Verulamium would continue to operate as a Town, although in a much denuded form from its peak, before eventually giving way to the emerging market Town of St Albans around the tenth century.