Public uses of Public Houses

For several centuries, many towns and villages lacked public buildings that could be used for civic purposes. Churches and pubs were often used instead – even, Jon Mein explains, as temporary mortuaries.

Friday 29 September 1905 was a sombre day at the Midland Railway Hotel. Meeting at this Victoria Street pub were the coroner, inquest jury and members of Cyril Dixon’s family. This four-year old boy had died two days earlier, severely burned when his woollen and cotton clothing caught fire.

While the cause of death was far from unique, what is worthy of general note is that his inquest was the last of many hundreds held in public houses in St Albans. This was common practice in England which, in local terms, dated to the late 1700s and probably before. Why had it come to an end? The timely coincidence of two factors provides the answer. Firstly, there was the introduction of new facilities.

Ubiquitous pubs used when civic mortuaries were lacking

Pubs played a key role before civic mortuaries were readily available. They were convenient in often having space to store the body until the inquest was held and to host the inquest itself. Moreover, due to their ubiquity in the Victorian period especially, pubs were often the only suitable premises close to the scene of the death. Convenient certainly, but conditions could be far from perfect.

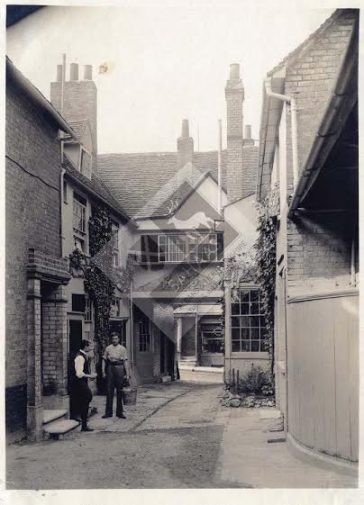

Take, for example, the case in 1898 of a man decapitated by a train close to the main station. His remains were kept at the Midland Station Hotel (now the Horn pub) in Victoria Street. Or the assistant schoolmaster from Hatfield Road Board School who in February 1901 accidentally poisoned himself. His body was left at the George Hotel in George Street (Fig. 1). Both corpses were stored in the hotels’ stables where, to make matters worse, the schoolmaster’s body appears to have been dumped on the floor without recourse to a coffin. The inquest jury noted that the body was laid out like ‘a horse or a cow’ and risked ‘being eaten by rats and mice’.

Cases such as these brought matters to a head. According to Dr Lovell Drage, the district coroner, a municipal mortuary was needed and he campaigned to force the city council to provide one. Such a facility would, he claimed, be more sensitive for the bereaved and suitable for increasingly sophisticated post-mortem examinations. The council acquiesced in the spring of 1901, funding construction of a mortuary behind the police station in Victoria Street (Fig. 2).

The second factor bringing the end of pubs as venues for inquest meetings was that of changing attitudes to their use in general. This practice was a regular occurrence in St Albans with, in the late Victorian period, an average of three inquests a year held in the city’s pubs.

Royal Commission calls time on pub mortuaries

But, by 1900, the end was in sight. The Royal Commission sitting in the late 1890s to consider liquor licensing reform heard that witnesses at inquests were known to treat themselves to their hosts’ beer before giving evidence. The commissioners called for this ‘scandalous’ use of pubs to stop. The Licensing Act of 1902 saw their demand put into effect stipulating that no pub was to be used after 31 March 1907 where other suitable premises were available.

A search of the digitised Herts Advertiser newspapers indicates that, poor Cyril Dixon’s 1905 inquest apart, the use of pubs in the city for this purpose ended in March 1902. This was still two months before the Licensing Bill was even discussed in Parliament. Who influenced the early change in St Albans is not clear. Even with their tendency to complain to the point of absurdity about public houses, the city’s noisy temperance campaigners appear to have kept quiet on the matter. They would have been content with the result though.

Over the next few years, the Town Hall and new semi-public buildings such as parish and mission halls replaced the city’s pubs as venues for these sad gatherings.

A fully referenced version of this article is in the Society’s Library. My thanks to Richard Mein and Alan Smith for their comments on an earlier draft of this article.