For most of the history of this area, the principal local administrative units were not boroughs but parishes, centred on parish churches. Until the population explosion of the nineteenth century, St Albans and its environs were sparsely populated, and parishes were much larger than they are today.

In this article, Kate Morris tracks the development of that part of St Peter’s parish within the borough of St Albans. The article is based on a talk given in October 2010 to the Friends of St Peters Church, St Albans.

The old Parish of St Peters

For much of its history, St Peter’s parish extended well beyond the confines of the town, all the way to Hatfield in the east, and to Sandpit Lane in the north. To the south it included Colney Heath and London Colney and to the west included the ‘backsides’ of St Peters Street properties, and Catherine Lane, with St Peter’s Grange lying just behind present day Chime Square, still reflected in the name of Grange Street.

St Peters was divided between the parish in the Borough and the parish in the Liberty – that part of Hertfordshire under the influence of the Abbey in medieval times but outside the town. The Borough was created formally, by Royal Charter in 1553, following the dissolution of the monastery in 1539, although the town boundaries were already understood by that time.

Parishes were charged with most aspects of local administration, but in the case of St Peters, responsibilities were shared in the urban area, which formed part of the Borough of St Albans.

The Borough was divided into four wards, of which St Peters coincided with the parish within the Borough. The Borough’s northern boundary ran broadly with that of St Peters, but, from Stonecross, ran back along Bowgate, or the top end of St Peters Street, taking in only the properties bordering the street and the church itself, and continued down what we now know as Upper Marlborough Road and down towards the river Ver.

The tightly knit urban area – St Peter’s Street and its backsides with just a small number of side lanes – has been the target for research by a small group of members of SAHAAS. St Peter’s Street commences at the corner of Dagnall Lane, the corner with W H Smith, and opposite, in Lamb Alley, can be seen the marker on a beam above head height which indicates the boundary with Abbey parish – necessary evidence when, with the provision of welfare resting with the parishes, the return of paupers to their parish of settlement was common.

By the late nineteenth century it was rather more built up and the first OS map, drawn 1878 but not published till a little later shows great detail – so much so that it comes in several sheets, making it difficult to show the parish conveniently.

Saxon and Norman origins

The urban parish coincides with that area which was laid out, probably by a Norman abbot, following the establishment of St Peter’s church by a Saxon predecessor, as a market, much as developers might do today, with more or less uniformly sized plots around the market with frontages of either a perch (16ft) or sometimes 26ft, for occupation by artisans and others, outside the monastery precincts, and with a large open area in the middle and terminating in the North, with the church on the East side.

It included farms – part of Towns End, St Peter’s Grange, the house at Hall Place, and indeed the farm of the manor of Newland Squillers, with its house on the site of the present day Marlborough Buildings in Hatfield Road. Whether the farmland was regarded as part of the town prior to the Dissolution I rather doubt, since the boundary was tightly drawn. A ditch cuts through what is Chime Square today and it would be logical for that to have been the Borough Gate, or Town’s End.

The Abbey parish

The Abbey parish, by contrast, was always very small, a compact but densely populated area hard up against the abbey itself on the natural trade and military route from London to the Northwest, which probably grew more organically. That route led from St Stephens in the South, to St Michael’s in the North and it was flanked around the monastery by inns to accommodate the many travellers. Whilst St Peter’s Street today is seen as a through route, an alternative to the M1 in times of traffic chaos, it was, in fact, historically, not so. St Albans has been described as a thoroughfare town, but most through travellers would have stopped over and their route would not have included what is today St Peter’s Street. The continuing success of our market today evidences this.

Roads and traffic

Coaches and wagons probably did not litter St Peter’s Street, though horses and other livestock would have done. Until well into the nineteenth century, access to the area from the principal through route, or Watling Street, was through the Market Place or French Row, which must have been very congested.

What we know as Chequer Street was also congested, and, for a time, virtually blocked by an inn called Red House. In the 1830s, there was an attempt to provide better access to the new Town Hall and Court Room in St Peter’s Street by cutting Spencer Street to link the new bypass (Verulam Road) with St Peter’s Street.

Despite the purchase of the Abbey church by the Borough following the Dissolution, St Peters probably remained the church of the town and the townspeople. It stands proudly at the top of the town and provides a vista in all direction. It can be seen from afar. Many prominent citizens chose to be buried there, and indeed burial facilities at the Abbey were limited.

St Peter’s Street in the 17th century

Benjamin Hare’s map of 1634 is the first known detailed map of the town. It is thought the buildings shown are notional but they give a good idea of where there was habitation. In the 17th century it would certainly all have been rather more rustic and relaxed than now, though active and prosperous.

Though a wide and open street, the plots on St Peters Street were, in the main of limited width. There could, in many cases, have been access from the rear, but in few cases would there have been side access from the front, as we see with old inn buildings, for instance down Holywell Hill.

This would have been an issue for some trades and we know that it led to trade activity in the open area. A seventeenth century court book shows no fewer than four carpenters in St Peters presented for creating sawpits on the King’s Highway and storing wood in front of their premises. Dung was a valuable agricultural commodity and this was often stored in the street.

Nine such heaps were noted in St Peter’s Street in one record. Some people felt the need to provide shelter for themselves or the goods they offered and built lean-tos in front of their houses, whilst others erected railings to provide a private area as a forecourt.

Whilst there would have been no paving, there were demarcated wastes, such as we still see today on Sandridge Road. We know that trees were grown along some frontages, which were there either as a personal amenity, or subsequently traded as timber. So whilst there would have been a bustling and maybe rather dirty atmosphere, there were also amenities, and the ambience of the principal open area would have been more that of community activity than of a thoroughfare.

Water supplies

From the late seventeenth century till towards the end of the nineteenth, there were ponds along the street – Upper Cock Pond (in front of the Cricketers) and Lower Cock Pond (in front of the War Memorial), and White Horse, or Monday Pond more or less outside Marks and Spencer’s.

These were filled by springs and wells, mostly to the north on Bernard’s Heath though in the early eighteenth century water was also pumped from the Ver through lead and wooden channels along the line of Marlborough Road up to Cock Lane (Hatfield Road) and into these ‘cisterns’. Marlborough Road follows the line of Tonman Ditch, the old defence which formed the Eastern borough boundary and the line of the ditch was a convenient route for these channels, avoiding disruption to the main roads.

The ponds met some of the needs of residents and the livestock brought to market, but was also an important resource for fighting fires in the town. Maintenance was the responsibility of adjoining residents and businesses, though they were sometimes also leased to aldermen of the borough.

Two public wells were also located on the street, one just to the south of the church, which was mostly the responsibility of the parish, and another outside what is now the Museum and Gallery in the old Town Hall. They were in use until piped water was more generally available from the water company at Stonecross in the late nineteenth century.

St Peter’s Church (1840s), showing well house in the foreground

The well on St Peter’s Green was protected in a well house, until a Braithwaite pump was installed in the 1880s. There was no Green as such, with grass or trees until the very late nineteenth century, though there were trees in the churchyard itself.

Pemberton Almshouses

Pemberton Almshouses, Bowgate

In 1627 Roger Pemberton had died and left land and money for the erection of almshouses. Their location is shown on Hare’s map and they are still there today opposite the church, and now part of the District Council’s housing stock.

The parish was to administer them and did so until they were taken into the Council’s care immediately after the Second World War. The rather prominent Pemberton family – Roger was High Sheriff for the County, and his grandson Robert, a Mayor of the Borough – were associated with St Peters and were buried here. St Albans was, then, in the main, a town of Dissenting opinion, for the Commonwealth and supporting Cromwell, and the Pembertons followed that line. Robert was granted a licence to hold religious meetings at his house in St Albans in 1672. This was probably close to the corner of present day Victoria Street.

The Saracen’s Head and its environs

In 1637, Robert Haile, about to sail abroad, made a will and referred to his inn The Saracen’s Head at Bowgate. Gerard McSweeney’s research places this inn also opposite the church, though no visible sign remains. Churchwardens’ accounts show that in 1660 a James Aggleton was paid 10 old pence for work to the churchyard wall over against the Saracen’s Head.

In fact, McSweeney has proved that, at that time, there were two inns, the Saracens Head and the Black Bull, and a handful of cottages on the site of Ivy House and its grounds. They occupied the whole site between the almshouses and the vicarage, where today we have a parade of shops and residential close as well as Ivy House itself, which is the offices of Debenhams, Ottoway, solicitors.

From the Hearth Tax return of 1663 we know that there were four houses in St Peters Ward with more than ten hearths. Dr Thomas Arris’ house in Bowgate with a frontage of 120 ft had eleven hearths. This was Hall Place. The other three were probably the manor house of Newland Squillers, the vicarage and one other, perhaps The Grange (Nationwide Building Society).

Within the ward fifty eight houses were assessed. In comparison in Middle Ward, a smaller area, there were ninety but only two with more than ten hearths, which shows how densely populated the Abbey parish was, compared with St Peters then.

Gerard McSweeney comments on the inns we have mentioned:

Together with the Cock nearby, all were smaller than the large Holywell Hill ones so I think they probably catered, not for the long-distance travellers but included those bringing their goods and cattle to market from the north and east.

Localism applied to St Peters then. It was prosperous, salubrious, and focussed on the market.

So we have the open space of what is now St Peter’s Street, truncated by the churchyard wall, surrounded by some rather large houses, interspersed with smaller dwellings, cottages, inns etc, with Bowgate leading north, boasting a handful of larger properties and farmland. But, at least from around the 17th century, we see the Borough and the parish boundaries as pointing rather awkwardly outwards from a natural line to reach what we understand to have been a Stone Cross marking the extremity of the community and where the gallows are said to have been. Beyond, lay Bernard’s Heath and Sandridge parish.

The boundary of the Borough would, perhaps logically, have been just beyond the church, maybe to include Grange Farm, maybe, or not, to have included Town’s End farm, but certainly culminating before the fork where the highway divides to lead to the West to Luton and to the East to Sandridge or Hatfield and Colney Heath.

Snatchup

Although Hare’s map does not show dwellings there, we know that a further cluster of plots did exist beyond that logical boundary owing homage to the Lord of the manor of Newland Squillers, certainly by the second half of the 17th century. Hare includes the area within the borough, in that fork, and beyond. That cluster of plots became known as Snatchup.

There is much speculation on the name of this small enclave, but I have concluded that it is a local Hertfordshire term for what is more often known as an encroachment. Being highway land, it is not difficult to imagine dwellings emerging at this entrance and exit to the Borough, just as the market infill gives us French Row and Market Place at the other end of town. This may only have happened since the Dissolution when new secular landlords were happy to see new dwellings, and charge rents and surrender fees for plots which fell in the manorial territory but were, strictly speaking, on highway land.

Once established, they were gradually incorporated within the parish and borough. So, by 1753, Phillip Shepherd was paying land tax in St Peter’s Ward for his house at Snatchup End, and the steward of the manor of Newland Squillers was recording transactions at his Court Baron in respect of cottages along the highway, all recorded in the 19th century censuses as at Snatchup Alley.

A similar 17th and 18th century Snatchup end at Kings Langley, also now built over and changed, seems to endorse my theory. That this would have been a natural gathering point, where the services of a blacksmith, joiner, gardener etc and later a beerhouse or two, is clear and is illustrated by a painting by J H Buckingham.

Developing road network

Around 1700 the road to Hatfield, then known as Cock Lane was upgraded to provide a passable route connecting the Great North Road with the Bath Road via St Albans and Watford to Reading and this was later turnpiked. It allowed those from east of here to travel to spas of their choice in the West without the onerous journey into and out again of London. St Peters was now on another national route, if only as an early London bypass for the elite. Two hundred years later it, and Catherine Lane, would be widened to provide a direct through route, East to West, and lead to the expectations that car drivers have of our roads today.

Coaches and wagons probably did not litter St Peter’s Street, though horses and other livestock would have done. Until well into the nineteenth century, access to the area from the principal through route, or Watling Street, was through the Market Place or French Row, which must have been very congested.

What we know as Chequer Street was also congested, and, for a time, virtually blocked by an inn called Red House. In the 1830s, there was an attempt to provide better access to the new Town Hall and Court Room in St Peter’s Street by cutting Spencer Street to link the new bypass (Verulam Road) with St Peter’s Street.

18th century prosperity fosters development

New building with brick and tiles

Ivy House, St Peter’s Street

The early 18th century was a prosperous time, with much new building, and now in brick and tiled, which was both fashionable and more secure against fire than the traditional timber and thatch. Ivy House was built in 1719 on the site of two previous houses.

Claimed by earlier Pevsner editions to have belonged to or been built by Edward Strong, master mason, who had worked with Christopher Wren on St Paul’s Cathedral, it was in fact the mansion of Rev Robert Rumney, vicar of St Peters from 1715 to 1743. More used for business and entertaining, its kitchen was for long the Saracen’s Head Inn which Rumney bought along with the new built house. Later occupants added the grounds up to the almshouses, demolishing cottages and the Black Bull inn to provide a beautifully landscaped garden, which stretched back to what became Church Street.

In 1732 the Duchess of Marlborough acquired the manor of Newland Squillers, though continued to reside at Holywell House down by the river. She instantly pulled down the manor house, opening premises there for veterans of her husband’s wars in 1736 – our Marlborough Buildings, still an independent charity.

The backsides of houses on the East side of St Peter’s Street were longer as one travelled south.

The grounds of The Grange, not to be confused with St Peter’s Grange, further north on the West side, occupied the land behind the street and north of Shropshire Lane (now Victoria Street). In 1763, John Osborne, sometime Mayor, built a substantial brick residence on this estate, now Nationwide Building Society. Barclays Bank, the Civic Centre, Alban Arena, Magistrates Court and Water End Barn fill what were the stables, out offices and gardens of the house. Dalton’s Folly, or Bleak House, on Folly Lane was built in 1706.

Brick facades added to timber-framed houses

Many other older houses were re-fronted in brick around this time as fashion absorbed the new styles and building regulations. The stretch of St Peters Street south of the old vicarage well illustrates this point, as does No 1 St Peters Street, sometimes known as The Mansion, with its little balcony overlooking the market. There are timber framed structures behind the facades, often evident by the steepness of the roofs.

Breweries, beerhouses and workhouses

However, not all building in this part of town was for grand purposes. In 1764 a workhouse was built for the parish, still standing as Rumball Sedgwick Estate Agents. By the 19th century, there were two breweries in and around St Peters Street in the 19th century and a whole host of beerhouses, many of which will have brewed their own beer.

19th century brings accelerated growth

Surveyor John Horner Rumball came to the town in the early nineteenth century, seeing scope for development. He worked alongside Godman, who redrew Hare’s map, working on tithe and estate maps. His personal opportunities lay around St Peters. He lived at what is now Anastasia’s restaurant and with the advent of the Union in the 1830s making the workhouse redundant, was able to purchase that building for his offices. He also bought the immediately neighbouring cottages, which are of a slightly earlier build.

Classical architecture comes to St Albans

Into the nineteenth century St Peters was becoming rather grand, though St Albans was still a small town, say 3000-4000 inhabitants. As a town it was relatively self-sufficient. The Borough had aspirations to becoming the County town, and, to this end, won for itself the new Court House, which would also supersede the old 16th century town hall or compter, (now W H Smith).

Classical architecture came to St Albans. George Smith was engaged to build the new hall, and went on to build the White House, opposite the church, to replace an old building, which had been run by two gentle ladies as a girls’ school. What is now the barber’s shop and the cosmetic dentist next door, was a boys’ school. The White House became yet another gentleman’s residence. Amongst others who lived there would be William Page, editor of the Victoria County Histories. The mid seventeenth century vicarage must have been crenellated around the same time.

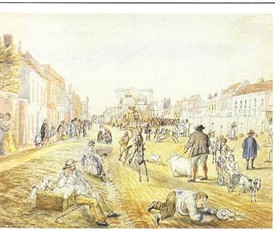

Michaelmas (Buckingham, St Albans Museums)

That it was still, nevertheless, a fairly rustic agricultural town, can be seen in further paintings by Buckingham of the Michaelmas Fair in St Peters Street, and also St Peter’s church. These markets, fairs and festivals have survived though the post-agricultural era, keeping the town alive for residents and visitors alike.

Buckingham strangely shows no trees at all in St Peters Street, though there are footpaths to the side. The wastes are perhaps illustrated where the man is lounging on the outer side of the drain, which must have fed the ponds. That, in itself, illustrates how wet the open space must have been and the need for sponsorship to provide tree coverage.

St Peter’s Church from Clifton Street (Buckingham, St Albans Museums)

He also provides us with a view of the church from what is now Clifton Street or Hillside Road showing the rustic nature of the surrounding area.

Genesis of the avenue

St Peter’s Street was described in the nineteenth century as one of the most beautiful avenues in the country and protected and enhanced as such in various ways.

St Peter’s Street, St Albans in the 1880s

In September 1881, a lead article in the Herts Advertiser called for enhancements to the city centre, including trees, with their health-giving properties, to encourage new residents and visitors, St Albans having been slow to grow. A prosperous new resident, Henry Jenkyn Gotto, had offered to donate an avenue of trees for St Peter’s Street if the Corporation would plant and maintain them.

This proposal resulted in much debate about burdens on the ratepayers and several years passed. But, following the article, agreement was reached on the proposal, with members of the Council’s Tree Committee finally settling on a plan for an avenue of limes, which would amongst other things provide nectar for the bees. By this time however, members of the Committee had individually to sponsor them.

Tree planting: “The proposal to plant each side of St Peter’s Street with trees has taken practical form this week. The Tree Committee gave the order to Mr Watson of Hatfield Road, and it being reported to the Town Council meeting on Wednesday that the necessary contract had been signed, the work has proceeded during the last few days.” (Source: Herts Advertiser, 3 December 1881, p. 5)

Aspirations in the affluent parish of St Peters brought demand for more and more and grander and grander pews in the church, and this led, in 1803, to the tower of the Saxon church falling down. A major restoration was undertaken, but less than a century later, more work was required. Lord Grimthorpe funded this and introduced the present Victorian Gothic structure. The tower by this time was supporting no fewer than twelve bells, a fact echoed in the name of the little beerhouse across the road, next door to Mr Rumball and his successors (part of the block which is now the carpet shop). It was called The Twelve Bells.

Development driven by railways and industry

The residential and industrial development driven by the advent of the Midland Railway to the town in the 1860s was largely in St Peters parish, though not all in the borough. Straw hat factories abounded with some in St Peters Street itself.

Wall Close on the south side of Hatfield Road was the earliest residential development with Manor Road, Hillside Road, Lemsford Road, and Hatfield Road following, all laid out with many splendid architectural examples.

On St Peter’s Street itself, Thorne House was built where the Post Office now is and Aboyne Lodge was just a little further South than Adelaide Street, with gardens on the backside, which the owner opened to the public for a small fee. Donnington House is now part of the National Pharmaceutical Association.

Demand for development continued with a feeling in the town that it needed to catch up, since the railway had come later than to some towns. Lord Spencer, still Lord of the Manors of Newland Squillers and Sandridge, was persuaded to give up agricultural land for all this residential development.

Better utilities

Gas had come to the town in the early nineteenth century, and the water company, which had taken over the whole of the Snatchup area for its boreholes, tanks and engine houses, was servicing the new residential demand for quality services. The ponds in the town were gradually filled in and wells no longer required. In 1898 the area we now know as the War Memorial Gardens was laid out with shrubs and enclosed with railings.

Changes to St Peter’s Green

There are many illustrations which show the Green before Lower Cock pond was filled in in the late 19th century, and a handful of years later, the widening of both Hatfield Road and Catherine Street took place. A number of dwellings and shops were lost at the time of that widening and then, in 1921 the War Memorial was erected. In 1930 the current owners of the beerhouse and blacksmith’s forge, by then on the corner, pulled down the buildings and built our local The Blacksmith’s Arms.

The church pulled down the remaining one of the three cottages of the sixteenth century Cox charity close to the church and built the Church House we see today. Sculleries and adjacent toilet facilities with running water replaced the standpipes and latrines at the bottom of the gardens in the old cottages on the Green, and in the 1950s and 60s improvement grants allowed the introduction of bathrooms to those houses.

The increase in traffic brought destruction of corner properties on the opposite side of the road with the loss of the Painters Arms on the south corner and the bakery on the north side, and the little Twelve Bells beerhouse had also been replaced by then. Instead we acquired vast shop units with offices above and of little character on each side, demonstrating to those approaching from the East that St Albans, and St Peters was now firmly a part of post-war Britain.

Late Victorian and Edwardian eras

Fine houses and grand banking halls

Hall Place, St Peter’s Street

The late Victorian and Edwardian eras brought ever more development such as the fine houses on the site of Hall Place and its grounds and the house at Towns End, many designed by local architect Percival Blow. One, Thorne House, was a replacement for the one further down the street, where the Post Office then appeared, with its characteristic architecture; the banks built grand halls – Westminster, Lloyds and the Midland.

New churches

New churches were built for several denominations. The Baptist church at Dagnall Lane, Marlborough Road Methodist church and the Salvation Army citadel were in the town centre research area. Trinity Congregational church was on Victoria Street, close to the Midland Railway station and St Albans & St Stephen Roman Catholic church was built on Beaconsfield Road.

New schools and a library

A Carnegie library was provided in Victoria Street and an Art School where the maltings had been.

School provision of all kinds, with a British school in Spencer Street and a national school on land given by Lord Spencer on Hatfield Road. Both of these were overtaken by the building of a Board School on the Hatfield Road site in the 1880s, and then there was the opening of the Garden Fields School in what is now the Jubilee Centre on Catherine Street. The High School for Girls located early in the 20th century in Townsend Avenue alongside the Edwardian residential developments.