In the early afternoon of Tuesday 21 October 1845, several clerics and a few lay gentlemen set out for the Abbey Rectory, the home of Dr Henry Nicholson, to attend the first general meeting of the St Albans Architectural Society [1].

The idea for a Society had been under discussion for some time, and had gathered pace with the meeting that summer of a planning group at Sandridge Rectory, home of Revd Charles Boutell. Charles had held the curacy there from 1837. As a member of the Oxford Architectural Society and Hertfordshire Secretary to the Archaeological Institute in London, he already had demonstrable expertise, so it was not surprising that he was asked to join the group [2].

Charles might have walked from Sandridge – most people then wouldn’t have thought twice about strolling that distance – but as a man of some status with a reliable if modest income, he probably rode a horse. He carried with him some books and documents he planned to give to the nascent Society – six lithographs of English Domestic Architecture donated by his father, a clergyman in Norfolk; a collection of brass rubbings; a copy of Ackerman’s Numismatic Manual; and a sketch of certain armorial ensigns displayed on the ceiling of the Choir of the Abbey Church [3].

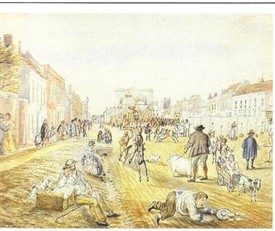

The Green by St Peter’s Church

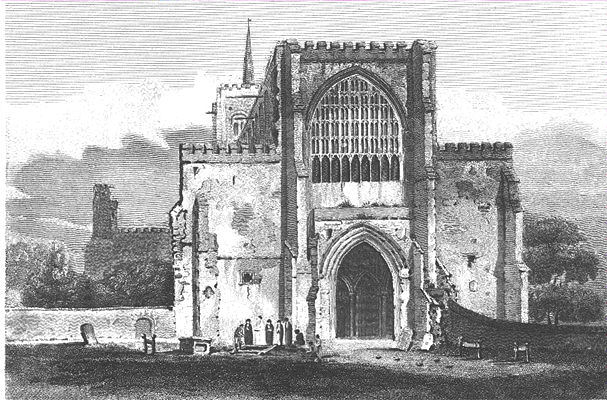

St Peter’s Church

Nearing Stone Cross, he would have seen the dilapidated medieval church of St Peter’s. The old medieval tower had been replaced by a brick tower early in the century, the transepts had been pulled down in 1812, and the chancel shortened [4]. But the largely Victorian structure we know today would not appear until the 1890s.

St Peter’s Street

St Peter’s Street (Buckingham, St Albans Museum)

Beyond the church was the broad St Peter’s Street, not yet an avenue and still unpaved. Fortunately it was not market day, so Charles did not have to contend with cattle, and the dung they had deposited the previous week would have been collected by thrifty gardeners.

The new Town Hall

At the end of St Peter’s Street stood the impressive Georgian Town Hall, which housed assembly rooms, a courthouse and a police station, as well as municipal chambers fit for the Corporation of the larger borough which had come into being in 1835. The borough of St Albans was now divided into four wards (largely following parish boundaries). However, neither municipal nor Parliamentary reform had done much to remove the stain of corruption on local politics. Had Charles been one of the relatively few electors within the Borough, he might well have benefited from the rampant bribery at election time.

Be that as it may, gentrification of the area, which had begun in the 18th century, was continuing:

many other older houses were re-fronted in brick around this time as fashion absorbed the new styles and building regulations. The stretch of St Peters Street south of the old vicarage well illustrates this point, as does No 1 St Peters Street, sometimes known as The Mansion, with its little balcony overlooking the market. There are timber framed structures behind the facades, often evident by the steepness of the roofs.’ [5]

House improvements and new civic buildings were not the only signs of changing times.

Change for the better …

Poor Law union

The imposing new premises (built between 1836-37) of the St Albans Poor Law Union at Union Lane (now Normandy Road) catered for indigents from a broad area, replacing separate workhouses for Harpenden, Redbourn, Wheathampstead, and Sandridge, as well as the old workhouse for St Peter’s parish in St Peter’s Street [6].

Better roads

And the road network was evolving. By 1845, the principal roads into and through St Albans had been turnpiked – toll gates like this one at the junction of Old London road and London Road ensured that non-exempt users paid to travel over the improved roads [7].

Old Toll Gate, London Road

Less than ten years earlier (1837), Holywell House had been demolished, allowing Holywell Hill road to be straightened and traffic to return from the diversion around Grove Road [8]. Verulam Road (1826) had been cut through Dagnall Street, providing much easier passage to the north of the town than Fishpool Street.

… and for the worse

But, despite its proximity to London, St Albans had not benefited fully from the industry and railway-fuelled development that towns like Watford and others further afield had experienced. True, there was a growing straw hat industry, based on straw plait made by villagers around St Albans and sold to commercial buyers in the local market. But industrial development was in its infancy, and St Albans remained relatively small, with a population in the region of 7,000 [9].

Coaching inns badly hit

Royal Mail coach that operated between London and York (DanieVDM)

The coaching inn business had already been hit by turnpiking and better road maintenance. As a result, St Albans had become a brief stop for refreshment for coaches from London rather than an overnight halt. Understandably, this cut down the business not just for coaching inns, but also brewers, farriers, comestible provisioners, brothels and others.

The pain wasn’t equally felt. Road improvements, such as the building of the new London Road (1796), benefited some inns (such as the Peahen), but drastically affected the business of those situated along the old London Road (Sopwell Lane). The same thing happened when the opening of Verulam Road in 1826 enabled coaches to avoid the pinch points in both George Street and Fishpool Street [10].

Mail services diverted to the railways

To add insult to injury, the opening of the London-Birmingham Railway a few years ago in 1838 had resulted in the diversion of much postal traffic to the railways, so mail coaches no longer called at St Albans. Other national road carriers too would have switched freight services to rail, relying on local carriers for the final leg of the journey. And St Albans still did not have a mainline rail station.

Stench of sewage and tallow fat

As Charles approached the town hall, his nose would have reminded him that St Albans still lacked mains sewerage. The effluent from the slums of nearby French Row and Gentle’s Yard (now Christopher Place) either drained into cess pits beneath the property (often contaminating the sub-soil) or was stored outside in readiness for collection by the night soil carts. Adding to the malodorous stench (particularly in the summer) was Edward Sutton Wiles’ business as a “tallow chandler and melter” in French Row [11].

“Sir, amongst all the nuisances in this town, the Candle Factory, situated at the corner of Verulam Street [now Verulam Road], is one of the worst. In all towns where sanitary laws are enforced, a factory of this kind would have been removed long before, and so it ought here. There are few mornings one can walk along the High Street without being annoyed with the awful smell of melting fat, which to most tastes is very disagreeable. I was walking along the Verulam Road and High Street towards London Road last Saturday morning and the stench was worse than ever.” Source: Herts Advertiser, 5 January 1868, p.8. Note: the operation moved in the 1890s

Doubtless Charles steered a course well away from French Row. Not only were the houses there little more than slums, but they housed some of the poorest people in the town – the sort described by Charles Booth in his map of poverty in London as vicious or semi-criminal.

By the late 1830s, slum tenements housing filled the former innyard of the Christopher public house. In 1838 the council was asked to resolve the ‘nuisance’ arising from the overcrowded state of the Christopher, which then housed 10 families, mainly paupers, eight of whom were suffering typhus fever. It reopened as a beerhouse in 1840, and the landlord Neptune Smith subsequently found himself accused of running a brothel as the Herts Advertiser reported on 7 December 1861[12].

Nearing the Rectory

Charles might instead have passed through the Market Place. Just past The Boot public house was the dilapidated but very necessary town water pump, worked by cranking a handle. The pump was sheltered by a canopy, and lay close to where the Eleanor Cross had stood until the middle of the 17th century.

Abbey Rectory, Sumpter Yard (Peter Bourton)

Assuming he was on horseback, Charles would have avoided Waxhouse Gate. Even on foot, there was no direct way through to Sumpter Yard (where the Abbey Rectory lies), so it would have made more sense to go down to Holywell Hill, and turn into Sumpter Yard, opposite the White Hart.

Charles arrives

Arriving at the Rectory, Charles would have greeted those taking part in the meeting. Before the meeting got underway, there would have been time for a cup of tea and some gossip about the issues of the day. And there was plenty to talk about. Two pillars of the Establishment – the Anglican church and the Conservative Party (as the Tory Party had become in 1834) – were in ferment.

Earlier that month, John Henry Newman, a prominent churchman and academic, had shocked Anglicans by deciding to take the next step in his long journey from evangelical Calvinism. He left the Church of England and was soon ordained as a priest in the Roman Catholic Church.

Meanwhile, a long-running issue that had divided Parliament for some years – the morality and effectiveness of Corn Laws that inhibited corn imports – was about to come to a head. Following the news in September that potato blight had ruined much of the crop in Ireland (and several other parts of the United Kingdom), the Prime Minister, Robert Peel, had summoned his warring Cabinet for an emergency meeting on 31 October to propose the distribution of emergency relief in Ireland – effectively an admission that the Corn Laws were unsustainable.

The meeting gets underway

Eventually, the Rector of St Albans, the Revd Dr Nicholson, would have called the meeting to order. He might have reminded those present that the now former Archdeacon of St Albans, Dr Charles Burney, on what might have been his last visit to St Albans before his transfer to Colchester in August 1845 [13], had encouraged his fellow clergy to form the Society, in the hope that it could do something to help ‘preserve and restore the crumbling Abbey’ in particular [14].

No doubt there were few surprises, as there had been plenty of time to choreograph the officer appointments. By the end of the meeting, Charles found himself one of two Joint Secretaries, a position he occupied until he left under a cloud in 1847.

Inspection of the Abbey church

Immediately afterwards, the members of the new Society went to inspect the Abbey Church. They might have taken the passageway that divided the former Lady Chapel from the area where the Alban shrine once lay, before it had been trashed at the Dissolution. The townspeople regarded this as a public right of way, and it wasn’t until much later (the 1870s) that the church was able to wrest back control, after the Grammar School had vacated the Lady Chapel and moved to the old Abbey Gatehouse.

The Cathedral passageway (Cathedral and Abbey Church of St Alban)

As they looked around the Abbey, they would have needed few reminders that it was in desperate need of repair. The condition of the nave was too dangerous to allow worshippers there, so services were held in the Crossing, though even that was in an increasingly perilous condition.

Quite what Charles thought about the situation we can only guess, though a Charles Boutell was reported to have written in the Building News in 1871 arguing against intrusive restoration: ‘Rather than that the Restorer [an arch reference to Lord Grimthorpe], with ample means and unrestricted powers, should work his will upon the Abbey at St Albans, let it share the fate of Kirkstall, of Fountains and Netley and Tintern and their sister ruins’ [15]. It’s unlikely that Charles would have been appointed a Joint Secretary had he expressed similar views at the first meeting of the Society!

The west end of St Albans Cathedral prior to the destruction of the Wickhamstede window, from “Beauties of England & Wales” London: Published by Vernor & Hood, Poultry, March 1, 1805 (Public domain)

In fact, it was not until ten years’ later, in 1856, that serious remedial work started under the supervision of Sir George Gilbert Scott. More extensive, and highly controversial work was undertaken in the 1880s, funded and controlled by Lord Grimthorpe. But that is another story.

[1] It is not unreasonable to assume that the meeting would have taken place in the early afternoon. This would have enabled attendees to travel to and from the meeting in the daylight, in an era when street lighting was sparse. Indeed, the Committee resolved at its meeting on 17 December 1845 that all meetings in 1846 would be held at 2pm.

[2] Notes of the meeting held on 21 October 1845.

[3] ibid.

[4] History of the Church – St Peters, St Albans [9 January 2020]

[5] St Peters in the Borough – a long view on its natural, built and cultural environment, Kate Morris, 2020

[6] The workhouse – The story of an institution, workhouses.org.uk/StAlbans/ [9 January 2020]

[7] A brief history of English Roads: the turnpike era https://tringhistory.tringlocalhistorymuseum.org.uk/Tring/c_chapter%2002.htm

[8] p327, David Dean, ‘Alban to St Albans, AD 800 to 1820’, in ‘A County of Small Towns’ , ed. T Slater & N Goose, Univ. of Hertfordshire, 2008

[9] 1841 census, St Albans Borough

[10] Jon Mein & Frank Iddiols, ‘Bottlenecks in George Street’, SAHAAS Newsletter 205, August 2017

[11] Recorded in rate assessments and a 1845 trade directory

[12] Debbie White, ‘The colourful history of St Albans’ long-lost Christopher Inn‘, Herts Advertiser, 31 January 2016

[13] p1, The Light of Other Days, Brian Moody, SAHAAS, 1995

[14] Archdeacons of Colchester (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archdeacon_of_Colchester)

[15] p 108, Asa Briggs, ‘The Victorian City“‘ in ‘Cathedral & City: St Albans Ancient and Modern’, ed. Robert Runcie, Martyn Associates, 1977.