Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough & her Almshouses

The Marlborough Almshouses

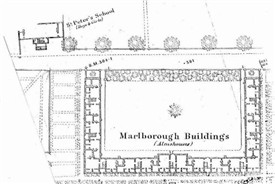

A prominent and familiar building in Hatfield Rd, St Albans, the Marlborough Almshouses (Fig.1 and a 19th Century drawing, Fig. 2) are named after the person who commissioned them, the formidable Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough. However it may be of interest, to those unaware of the details, to describe why Sarah built on the site, what was there before and who was the actual builder.

The Hare Map of 1634 (Fig.3) shows, in diagrammatic form, an important house on Cock Lane (Hatfield Rd.), standing in its own extensive walled grounds, bounded by the Tonman Ditch (the present Marlborough Road) to the east and stretching behind the houses down St Peter’s St to the south.

This was the site of the manor house belonging to the Manor of Newlane Squillers. In the late 1600s it was owned by Robert Robotham, Lord of the Manor. In his will he left the house and considerable property to his niece Ann, who married John Rochford, the Vicar of St Peter’s, and who leased out the house for her lifetime. That is the site of the Almshouses.

Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough

It is appropriate to begin this account with a sketch of Sarah and her activities leading up to the building of the Almshouses. Although she is quoted as being one of the most portrayed women of the period, it is possible that the one by Kneller is what might be called the ‘genuine’ one, (Fig. 4).

Nearly all the others are described as ‘after Kneller’, so presumably the artists put whatever gloss they liked on her. However, there is another, painted by Bernard Lens and dated 1720, when she was sixty. (Fig. 5).

An attractive painting but, after what was described as a long and combative life, with a fair amount of illness, she seems to have aged well or perhaps the artist was being complimentary. More prosaically, it could be a copy of an earlier oil painting celebrating her marriage to John Churchill, whose portrait is on her wrist.

The matchmaker

Apart from Sarah’s considerable political activities, she was an unwavering matchmaker. In fairness, most of it was aimed at preserving her vast wealth within the family and keeping it out of the hands of those of whom she disapproved. She said to one of her grandsons, Charles Spencer (the future 3rd Duke) (Fig. 6), (“now that you have dispensed with your mistress”) that she was “…glad that you have not so great an aversion to marriage … for our Family wants posterity very much” and she proceeded to survey the field for a wife.

Shortly afterwards, to his probable relief, she claimed to be too ill to receive him; ‘probable relief’ because he was in the process of sending her a message saying that he was negotiating to marry Elizabeth, granddaughter of Lord Trevor, a lowly Tory peer (Sarah was a Whig). Furthermore, the marriage negotiations had been deliberately carried out behind her back (this always rankled) and had been devised by her married granddaughter (Charles’s sister and Sarah’s implacable enemy). She was ‘volcanic with rage’ (Lord Hervey called her ‘Mount Etna’). The actual heir to her fortune was her favourite grandson and Charles’s brother, John Spencer, but he too had transgressed by attending the wedding. Furthermore, he refused to condemn his brother.

A few days later, John had second thoughts about this but Sarah refused to see him. However it was too late. She had literally burnt her will! One of her daughters said she had always thought her mother mad, now she knew she was. Albeit untrue, when the Duchess was in one of her famous rages, it seemed like it. All her children and grandchildren being now married or disinherited, the question was who was going to benefit from her wealth? The idea of the Almshouses was born and, before she cooled down, she wrote to the Attorney-General asking for the best way to do it.

Sarah’s charitable choices

The custom of rich people was to found a charity in the area of their birth and, in this case, the estate of Richard Jennings (Sarah’s father) included Sandridge. She had previously given some money to the veterans and families of Marlborough’s wars but was mindful of the comments that the Duke and his family, whose fortune came from those wars, had done little to help the sufferers. She wanted something more permanent. A good business-woman, she was not in the habit of throwing her money around but an additional incentive was provided as follows.

Sarah had bought the reversion of the Manor House of Newlane Squillers and, in a deed dated 2nd Sept 1732, she obtained an assignment of the lease. The London Evening Post reported in Feb 1733 that “…several workmen and other Artificers began to take down divers old buildings at St Albans by order of Her Grace the Dowager Duchess of Marlborough in order to raise a noble building for the relief of 40 poor families of the town and Her Grace will leave a sum sufficient to endow it for ever”. (Actually 18 men & 18 women).The reference to ‘families of the Town’’ and not the veterans, may have been a journalistic error but it has been suggested that this enlargement of the list of inmates may not have been unconnected with her considerable electoral interests in the town.

Ironically, with that volatility of temperament she often showed to her family, she was later reconciled with her grandsons when Charles Spencer, succeeded as Duke of Marlborough. Of the inheritance, £50,000 had gone to the building and, although she regretted her haste, it was too late to retract, in view of the complicated conveyances that had been carried out.

To find the details of a building’s construction, the obvious source is an account book, and many detailed financial accounts survive in the archives of grand families but unfortunately those remaining in the Northampton Record Office start at 1744, several years too late.

However, Dr Frances Harris has revealed the presence of a single entry in the Duchess’s account with the Bank of England. This was a payment of £500 to Francis Smith on 23rd June 1733 and reads, ‘For the Charity Buildings carrying out at St Albans’.

There is further evidence from an addition to the Deeds of Foundation, Orders from the Duchess: “to Christopher Lofft to execute at St Albans with Mr Smith, builder, dressers and shelves for the poor people must be taken out of the pollards and, if the pollards won’t hold out to the lengths prescribed by Mr Smith, three dressers must be shorter. As to the several works further to be done I desire Mr Smith would make such as he thinks fit; for I can rely entirely upon him and he may employ what workmen he pleases”. It mentions that at Harris’s and Thrale’s farms the holes made for bricks must be filled (following the common practice of local brick-making).

This example of Sarah’s attention to detail is emphasised by the injunction, “The Walnut tree must be brought to London”. In the 1826 Parish map (Fig. 7, area 2), 100 years later, the large area behind the east side of St Peter’s St was still called Walnut Tree Field.

Francis Smith of Warwick

She had already sacked Wren at Blenheim and quarrelled with Vanbrugh, so who was this Mr Smith, in whom she had such confidence?

A couple of years earlier, she was building a house at Wimbledon (Fig. 8) to add to her four others. The money for this estate came from astute buying after the collapse of the South Sea Bubble. Regarding this house, she disagreed with the architect again and, as usual, contracted directly with the workmen, calling in Francis Smith of Warwick. (Fig. 9).

A mason by trade, he had built a considerable reputation as a master builder and what would nowadays be called a quantity surveyor, with a diverse team working to his own or others’ designs; he describes himself as ‘architect’ by the time this portrait was painted. He was responsible for a large number of stately homes but, in the descriptions of his work throughout the country, there appears no reference to the Almshouses.He was, however, the sort of hands-on worker Sarah preferred.

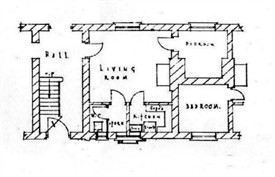

Smith was employed to oversee the completion, at least, of the Almshouses. Whether someone else was the designer is not clear, although the simple lines and brickwork, lately favoured by Sarah, suggests he may have been. The interiors of what we would call ‘flats’ are shown in the O.S.1/500 (1878) map (Fig. 10).

There is no main entrance to the building. Each external door leads to a small entrance hall and ground floor flat; a flight of stairs, to another one.

There is little more about the construction of the Almshouses, apart from a letter from her local agent at Sandridge, Thomas Kinder, (1734) who reports that, ‘The workmen at the buildings are letting them lie open for hogs, horses and cows to go in all round so fine a place’, an insight to the semi-rural area behind the St Peter’s St. houses. It was much the same 100 years later in the parish map already cited.

By the Deed of Foundation, four eminent trustees were appointed to administer the Charity. A Visitor was also appointed but the actual supervision was to be the Rector of St Albans or the Vicar of St Peter’s. The duties of the Trustees and provisions for their various activities were drawn up but they were irrelevant at that time as Sarah kept everything in her own hands as usual. The Trustees signed where she told them and, although she could draw up the rules for the inmates, she actually failed to do so. She used the Almshouses partly as a means of rewarding former servants and generally ignored the original aims of the Charity.

The Almshouses after Sarah’s death

When she died in 1744, it was a chance for the Trustees to take their rightful place as managers. However there followed years of problems, partially because they were upper-class folk at a distance from the day-to-day activities and partially in disputes about who should succeed as Trustees. There were also financial troubles.

The problem was that, although Sarah had taken the management of the Almshouses into her own hands, she left few instructions regarding their administration. In a lawsuit, one of the Trustees, Lord Winchilsea, remarked to the Lord Justice on “her unlucky thought of founding a hospital”. However, rules for the inmates were drawn up in 1761 and revised in the mid-1800s.

In the decades that followed, arguments regarding the appointments of Trustees and financial problems still beset the Charity. Although the choice of inmates had been made with local politics in mind, some veterans of the Peninsular War had been included. The family were still involved; the widow of Sarah’s great-grandson, the Dowager Countess Spencer, (mother of the famous Georgiana) who lived at Holywell House, devoted time and money to helping the Charity to the end of her life. Eventually, theSpencer family relinquished its connection with the Charity .

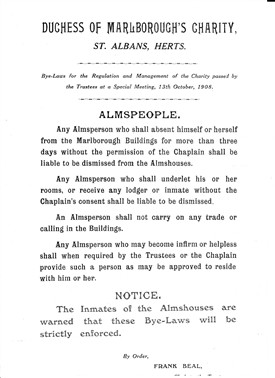

By 1908, some of the more restrictive rules had been removed and reference to these was made in a solicitor’s letter, now at Hertford, to the Vicar as local administrator, “It is entirely within your discretion as to whether an inmate should receive visitors or not ….. Mr Swan’s application does not seem unreasonable and the only question is whether it will create jealousy or lead to too many similar applications being made by other inmates”. It enclosed a card (Fig. 12) of the rules.

After all the vicissitudes of the past, the Charity Commissioners produced a schedule in 1955, replacing the early ones and detailing the all the conditions under which the Almshouses should be run. This specified nine “competent persons”, including the Vicar of Sandridge, ex-officio, and two appointed by the City Council.

So, we have to thank a family quarrel for one of the few 18th Century St Albans properties still more or less in its original form, although the outside underwent a transformation in 1850. Note the lack of a pediment in the early drawing by Oldfield (Fig.2). The rather magnificent present one was presumably erected at the time of the transformation (Fig. 13).It features a lozenge, the arms of a widow. The windows were apparently replaced with the present diamond-shaped panes. Although the apartments have been modernised to produce very cosy dwellings, the interior structure is virtually as built, as the staircases (Fig.14) illustrate.

Finally, one notes the main criterion for accommodation, “Almspersons must be over 60 and of limited means”.

I am grateful to Northampton Record Office for extracts from their catalogue of the Spencer Papers, to Hertfordshire Archives & Local Studies (HALS) for assistance & to the National Portrait Gallery and Blenheim Palace for help via correspondence. Thanks are also due to Dr Frances Harris for allowing me to quote from her biography of Sarah, “A Passion for Government”, and for personal help with some other material.