Hard times on the food front during the First World War

Life in St Albans, 1914-18

On the 23 December 1916 the Herts Advertiser published a letter from a desperate housewife who stated: ‘The sugar question has become quite a scandal. Last week I could not get even a pound of brown sugar, go where I would.’

Sugar was not the only item of food in short supply, as reported in the recently published book, St Albans: Life on the Home Front, 1914-1918, written by members of this Society and published by University of Hertfordshire Press.

At the start of the war Britain imported over 60 per cent of its total food supply. At that time only one loaf in five was made from home-grown wheat and the nation was almost totally dependent on overseas producers for its sugar, two-thirds of which was produced by the sugar beet farmers of Germany and Austria.

By April 1916 consumers were paying 9½ d for a 4lb loaf, almost three times the pre-war price. Despite this, bread was never rationed as it was thought that this would hit the working classes disproportionately and might affect morale. However, from March 1917 onwards it became illegal for bakers to sell fresh bread. Loaves had to be more than 12 hours old before they could be put on display. Specific instructions were laid down on how bread should be manufactured and flour graded, with various ratios of wheat flour to other substances such as rice, barley, semolina, rye or beans: in February 1918 a government inspector visited St Albans to instruct millers and bakers in the adding of potato flour to the mix. Quality could be variable, as noted by one contributor to the Herts Advertiser: ‘Can small loaves be re-pulped like paper? I ask because in very truth I purchased one which an axe would glint. It was as hard as marble, uncuttable and almost unchippable. I took it back and wondered what would be done with it in these waste-not days.’

The establishment in December 1916 of a Ministry of Food was an indication of a desire by the government to be seen to be doing something in the face of growing criticism of its apparent indifference to the problems faced by the general population. Things did not change overnight but from the spring of 1917 local food control committees were set up across the country. These committees provided a framework for co-ordinated administration at the local level; the first meeting of the St Albans food control committee took place on Monday 13 August that year. The presence of only one woman on the committee of 12 was a particular bone of contention. After much politicking, four additional members, three of them women, were invited to join.

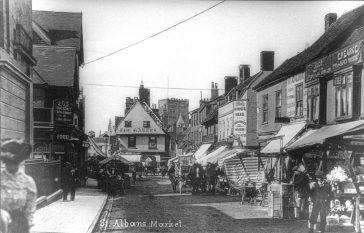

Perhaps the committee’s finest hour came three days before Christmas 1917. Word spread that the Maypole Dairy in Market Place had taken delivery of fresh supplies of margarine and a queue formed even before the shop had opened. Armed with new powers to seize stock, members of the committee arrived on the scene and took possession of the delivery, distributing it to other shops in the area. It was problems of distribution like this and the threat of unrest over unfairness that finally prompted the government to introduce rationing in 1918.

This article was originally published in February 2017 in the Herts Advertiser newspaper in a series of articles contributed by members of the SAHAAS Home Front research group. We are grateful to the newspaper’s editor for his permission to republish it here.