The man who found Verulamium’s theatre: Richard Grove Lowe 1801–1872

As part of the Society’s celebration of its 175th anniversary in 2020, we are publishing a series of articles on distinguished early members. In this article, Kris Lockyear looks at the contribution made to the Society by one of its earliest members.

Richard Grove Lowe was last of the four children of the Reverend Jeremiah and Anne Lowe, born on the 20th December 1801. In 1819 he became clerk to Thomas Witts Walford, an ‘Attorney at Law and Solicitor in Chancery’. After serving his five years as clerk he became a solicitor himself, based in St Peter’s Street.

As befitted his station he took on various positions in the town, including becoming Mayor in 1832 and 1841, and holding the post of Superintendent Registrar, Clerk to the Union and Coroner. Lowe was nominated for membership to the St Albans Architectural Society on 29 December 1845, six months after the Society was formed, and elected on 15 January 1846.

Lowe’s discovery of the Roman theatre

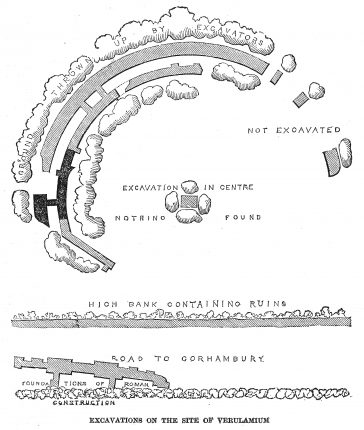

A special meeting of the Society’s committee was held on 16 November 1847 which recorded the “new openings within the walls of Verulam” undertaken by Lowe, and voted him the sum of £3 towards the costs. What he had found was the Roman theatre, the first example of its kind in the country. Lowe’s excavations created a great deal of interest, with both the Archaeological Association and the Archaeological Institute donating funds towards the costs.

On 29 January 1848 the Illustrated London News published an article on the excavations along with a plan of the remains as far as was then known (Figure 1). Lowe read a paper on the excavations to the Society on 12 April, which was then published by the Society — its first volume — later that year, along with an updated plan. The report published by Lowe received much praise at the time, for example in the Archaeological Journal (vol. 5, 1848, pp. 237–8), and especially for his care in “preserving a faithful narration.”

Lowe’s wider work

Subsequently, Lowe read papers to the Society on topics such as the excavations in the Abbey Orchard, the Second Battle of St Albans and Hertfordshire place names, but none of these was published. He was also voted 30 shillings by the Society in 1852 for an investigation of Watling Street but this does not seem to have taken place.

Although notes based on Lowe’s further observations at the theatre were published (e.g., Journal of the British Archaeological Association, vol. 6, 1851, pp. 91–2), or existed in manuscript form, Lowe did not publish an updated report on the findings at the theatre. He also made some useful observations on the Iron Age dykes around Verulamium, but again these remained unpublished.

Growing public interest in archaeology

The middle of the 19th century saw the foundation of many county archaeological societies, and the growth of archaeology as a subject. Although earlier antiquarians such as John Leland and William Stukeley are important sources, the spread of interest in archaeology amongst the middle classes at this time resulted in a great expansion in the preservation and investigation of archaeological remains and finds.

Lowe’s discovery of the theatre was important and, for someone with no training, his careful planning of the remains was excellent for the period. A more artistic recording was often employed (e.g., Figure 2). Unfortunately, the necessity of recording stratigraphy was not commonplace at the time, despite its application to archaeology as early as 1799 by John Frere. The excavations at Silchester by the Society of Antiquaries of London, in the late 19th century, employed a similar method of “wall chasing.” It is a shame that Lowe did not publish more of his careful observations and thoughtful ideas.

Lowe never married, and when he died in 1872 his estate went to his sister, Mary Emm Searancke. He is buried, where he was baptised, at St Michael’s (Figure 3).