To introduce a major exhibition in Autumn 2021 on ‘Chroniclers of History’ at St Albans Abbey, David Thorold, Curator of St Albans Museum, contributed the following article.

The pivotal position of St Albans

While many monasteries produced chronicles, few produced works of such depth and quality as those of St Albans – and certainly none did so for so long. St Albans had a number of advantages in this; it was close to London and with the presence of the martyr’s tomb, of high status, so that the king and his retinue as well as the leading barons regularly visited, providing the chroniclers with ample first-hand sources of accounts of national and international interest.

Many of St Albans’ abbots were powerful figures who strengthened the abbey’s position by developing political independence from both the king and the church, and increasing its landholdings. This also led to a need to produce records confirming St Albans’ rights and ownership of these estates.

The chronicles produced by the monks of St Albans served as the records of events of their church and the events that affected it, with an eye always to the interests of the monastery above all others. Their accounts are not unbiased, but their independence from royal censure means that they provide an alternative history to the actions of the elite.

St Albans’ size and status – it was the premier Benedictine monastery in England – meant that what might affect it included national and international events, and the monks recorded their abbey’s dealings with kings and popes with a similar bias – the Pope, although nominally their superior was considered greedy and far too influenced by the French; the king, although pious, was a fool who couldn’t be trusted to safely handle affairs of state.

Matthew Paris

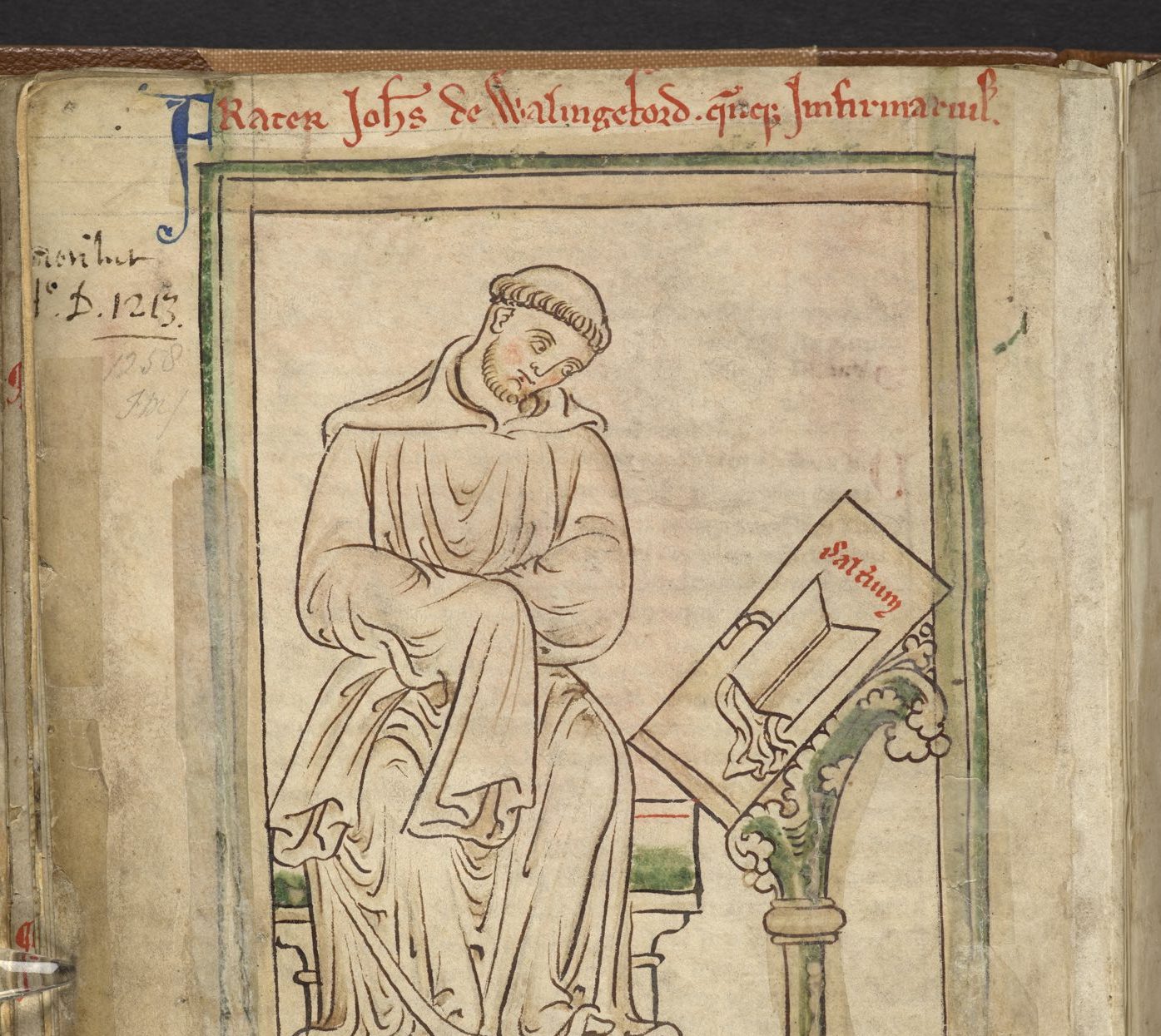

Self-portrait of Matthew Paris from the original manuscript of his Historia Anglorum (London, British Library, MS Royal 14.C.VII, folio 6r) [Public Domain]

Indeed, his fame was such that later in his life, Paris attempted to remove the more scurrilous comments he had made about his peers, as his works were beginning to be requested by individuals beyond the abbey – including the king!

Thomas Walsingham

Paris’ writings, and his equally skilful drawings encouraged the development of chronicle writing at St Albans for many years, but by the late fourteenth century, times had changed. Few monks produced books directly in their scriptoriums any more; instead illustrators and often scribes were hired in to produce works for them. Thomas Walsingham, the second great chronicler from St Albans, purposefully worked to reverse this state of affairs.

Directly influenced by Paris to such an extent that his major work, The Chronica Maiora shares its title with that of Paris’ magnum opus, Walsingham rebuilt the scriptorium and set about producing a second golden age of chronicling. His themes and biases were also similar to his predecessor, but by Walsingham’s time the world was changing and he is much more scholarly and academic. Being more aware of his biases and keen to show his learning in how he phrases his words – Walsingham’s account of the Battle of Agincourt is purposefully written to echo the style of classical Latin works such as Virgil’s Aeneid.

Unlike Paris, Walsingham also intended his works to have a wider readership and influence later writers – although he also felt the need to correct some of his stronger views against some important individuals, later in his life. From the early thirteenth century until the late fifteenth century, the monks of St Albans recorded events that affected them, and in the process wrote the history of England itself.