Business and philanthropy in 19th century St Albans

The Woollam family and silk making

In St Albans, Charles Woollam is remembered as owner of the local silk mills, a former Mayor and Freeman of the City, and a very generous local benefactor, but little is generally known about his life (1832-1915), or his family’s history of silk making. This is a story of remarkable family enterprise. There were in fact at least three successive generations of Woollams, each with a Charles involved in silk manufacture. There are also some references to other members of the Woollam family being involved with textiles, including one in Chester who dealt in flax.

In England, the conversion of silk cocoon filaments into continuous silk thread was, until the end of the 17th century, essentially a hand craft. Then some Italian secrets of mechanisation were discovered and copied, and the first silk “throwing mills” were set up in Derby and East Cheshire. In the latter part of the 18th century, industrial silk manufacture spread to many other parts of the country including Hertfordshire; the hostilities with France helped to increase the English demand for home-produced silk. In this international enterprise, the silk throwsters depended on merchants, mainly based in London, who would import the raw silk, and then sell the finished thread, at home or abroad. At that time the raw silk mainly came from China, but later Italian silk also became available.

The St Albans story starts with the first of these three Charles Woollams, who was in the 1770s a bachelor living in Wrexham Regis, and then described as a wine merchant. His antecedents are not known, but he could have been the Charles Woollam who was born in Whitchurch, Shropshire in 1732, son of another Charles. In 1777 he married a near neighbour, the widow of a Wrexham “draper and wine merchant”, Penelope Barber, who already had two sons, Samuel and Watkin Robert. At least four of Charles’ and Penelope’s children born in Wrexham died in infancy, but they raised two sons, Charles born in 1778, and John in 1788, also a daughter Penelope in 1783. Charles evidently took up and developed both parts of this dual trade, and he was described as “mercer and wine merchant”. In his Will he said that he had spent over £700 on the Wrexham premises by “sinking vaults and other improvements”. He also became involved with the London silk trade. From 1784 he had an office at 23 Cateaton St, London, with a partner Thomas Billinge; they were listed in trade directories as “Woollam & Billinge, silk men” and were presumably involved in the wholesale silk business. Cateaton St was just south of the Guildhall, and was much frequented by textile traders; it was later renamed, becoming part of Gresham St.

It is not clear how much of his time Charles spent in London, when he had a growing family in Wrexham, and commuting from there would be very difficult. It seems likely that he conceived and financed the operation, but left Billinge to do most or all of the trading. They were on good terms: in Charles’ Will, first drawn up in 1794, he appointed “my friend Thomas Billinge” as one of his executors. In the will, he described himself as “wine merchant of Wrexham”. He did not refer to any business interests or premises; this was usual, as wills at that time dealt primarily with personal estates and family matters, not with real estates, i.e. land and property.

The Woollams and silk throwing in St Albans

In spite of being a wine merchant, Charles saw the great potential for building his own silk throwing mill near to the London market, and had found a vacant site at the old St Albans Abbey Mills. Sadly he did not see his plans come to fruition, because he died in December 1797. But the work went ahead, and by 1802 the first of the new mill buildings had been erected, with machinery powered by water and by steam. It would accommodate a large work force, mainly of women and children. Work started in 1804, and soon a second mill building was added.

We do not know who was the driving force behind this project, but Charles’ elder son (also Charles, born 1778) evidently moved from Wrexham to St Albans to take charge. There are very few records of this period, but in 1812 a Charles Woollam was invited to become a St Albans Alderman (but declined), and in 1835 stood as a candidate for St Albans Council. After he died in 1836 his widow Elizabeth was recorded in 1841 as living in the Abbey Mill House.

At the same time as this, the silk trading firm continued to operate in London, trading first as Charles Woollam & Co, then as Woollam & Brothers.

In 1796 a codicil was added to the will, removing Billinge from the list of executors and replacing him with Charles’ wife Penelope. No reason was given. Then in December 1797 Charles died, and his son and heir would have automatically inherited at least part of his father’s real estate. The Woollam silk involvement in London continued: from 1799 there was a new firm “Charles Woollam & Co” trading as silk merchants at 39 Throgmorton St, near to Cateaton St where Billinge continued to trade separately at no 23. So it seems that young Charles had taken over his father’s interests very promptly – unless someone else was using the dead man’s trading name. By 1811 the new firm was styled as “Woollam & Brothers”, at a slightly different address off Throgmorton St. Charles had only one brother, so perhaps the plural indicates that the Barber half-brothers were also involved?

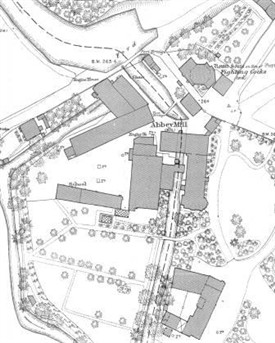

By 1802, the first Woollams silk mill had been built at St Albans with space for a large work force, mainly women and children, and powered by water and steam. Someone in the Woollam family must have seen the great potential of building a new throwing mill near to the London market, and had found a site at the old St Albans Abbey Mills. It seems likely that Charles senior had conceived this plan years before, perhaps knowing even then that his sons and stepsons would have to put it into effect. They would have needed the help of someone experienced in the technology of silk throwing, but their identity is not yet known; perhaps Billinge had something to do with it? The business evidently prospered, and a second mill was added some years later. The buildings are still there today, now converted into apartments, in positions where they could have been connected to the mill water wheel.

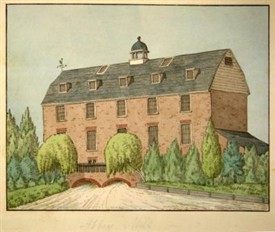

Abbey Mill c.1800. Courtesy of HALS – Oldfield Vol.8 pg.559

There is very little information about the previous history of this site. There was a mill there in Saxon times, if not before, operating from a man-made mill stream. In at least part of the Monastic period, there was a fulling mill as well as a corn mill, controlled by the Abbot, as well as a Conventual brewhouse. Archaeological evidence suggests that milling ceased on the site during the 15th century. No records have yet been found of ownership or usage after the Dissolution, but a mill is shown there on Hare’s 1634 map. There is also a 1671 inventory record of “Samuel Turner’s house by the Abbey Mill”, with upstairs heating, ie “barrs to burn coale with, in the chamber over the hall”. This may have been the predecessor of the present Abbey Mill House, which is thought to be built over medieval mill foundations.

The only direct reference I have found to the foundation of the silk mill came more than a century after the event. When the third Charles Woollam died in 1915, the Herts Advertiser report, no doubt written by local historian and editor A E Gibbs, included the following:

“For fifty years Mr Woollam had had the control of the Abbey Silk Mills, which for 100 years had been carried on in the name of Messrs C Woollam & Co. They were founded in 1802 by Mr Woollam’s father (Mr John Woollam), his brother, and his two half-brothers (the Messrs Barber), their father having been with the wholesale trade in raw and “thrown” silk for many years. The mill was started in conjunction with the London business, and by reason of its nearness to London – at that time and for many years after a central market for Asian raw silk – a flourishing business was established ” (Note: John Woollam was only 14 in 1802, so he could hardly have been the real founder. It was more likely to have been his brother Charles, then aged 24, and/or his stepbrothers.)

So far, no mention has been found of the Barber brothers in St Albans. It is not certain where any of the silk men lived at this time, but there was the Abbey Mill House available. There is a reference in the Corporation records that in 1812 a Charles Woollam was chosen as a St Albans Alderman, but declined to serve. Such a person would have to be an established St Albans resident, with adequate financial means; this sounds likely to have been our silk man Charles, then aged 34, probably living at the Abbey Mill House.

The name of Charles Woollam appears again in 1835 as a candidate (unsuccessful) for the St Albans Council. Then in 1836 he died and was buried at the Abbey, age given as 58. His widow Elizabeth was recorded as living at the Abbey Mill House at the time of the 1841 Census; her death certificate in 1848 confirmed that her husband Charles had been a silk throwster.

Meanwhile his brother John Woollam was living in Hampstead, which was then a rural community outside London. He was presumably running the office of “Woollam & Co., silk men”, which in 1840 was still at the same address as in 1811: 9 Warnford Court, off Throgmorton St. He had married a girl named Mary, who was born at Bristol, and they christened a daughter Penelope in 1825 at the parish church of St Marylebone, followed by John at the same church in 1827, then Catharine in 1830 and Charles in 1832. The parents’ place of abode was given in the baptismal records as Hampstead or Hampstead Heath. It seems that they regarded St Marylebone as their “family” church.

Presumably John Woollam inherited the silk mills when his brother died, and some time between 1841 and 1851 he and his family moved to St Albans. Their elder son, another John, was training for the priesthood, and the younger Charles continued his studies at St Albans Grammar School, being recorded there as winning prizes for mathematics and classics. In the 1851 Census, the family were listed at the Abbey Mill House, except for son John who was away at Oxford. Charles was listed as a 19 year old scholar. This young man, the third Charles Woollam, was destined to become our St Albans benefactor.

The 1861 Census showed John still in charge at St Albans, employing 360 hands, and Charles living at the Mill House with his parents, and also listed as a silk throwster. John died in 1869, aged 80, and was buried at the Abbey.

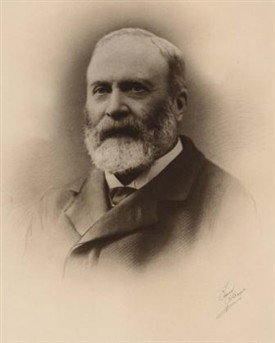

Charles Woollam Courtesy of St Albans Museum

In 1868 Charles was married in London (by his brother) to Mary Elliot. She had been born in Bombay, a daughter of Edward Elliot, who had been Accountant General of the Bombay Civil Service. At first Charles and Mary lived at Holywell Lodge, but by the time of the 1871 Census, they had taken over the mills and the Mill House. Charles was evidently interested to investigate the history of his site and some of his findings are included in Henry Fowler’s 1876 paper about the boundaries of the monastery.

In 1871 Charles was employing 419 hands in the silk mill, a figure which rose to over 500 some years later. The overseer at the mills was Frederick Peacock, who lived for many years in Orchard St, a row of silk workers’ cottages built in the 1860’s.

Abbey Silk Mills. Ordnance Survey 1:500 1879

The Woollams and the Grammar School

By now Charles was also becoming involved in civic life. In 1869 he was appointed as a Trustee of the Grammar School, becoming a School Governor for life. He and two other Governors were appointed as a committee to organise the transfer of the school from the Lady Chapel to the Gateway, which took place in 1871. Having lived in the town since childhood, Charles loved and wished to preserve its open spaces, and never lost an opportunity to acquire them in order to save them from “development”. One such important tract was the area known as Holywell Meadows, which had been part of the gardens and grounds of Holywell House. The last noble occupant had been Lady Georgiana Spencer, and after she died in 1812 the house was eventually demolished (in 1836), and the land offered for sale. In 1852 most of it was bought at auction by George Debenham, a solicitor and future Mayor of St Albans. By the time he died in 1883, the meadows had been reduced by developments on their north and west sides (Belmont Hill and Holywell Hill), and William Hurlock had acquired a broad strip on the south side to add to his Ver House gardens. The open space was then down to 7 ½ acres, and in 1886 Charles Woollam bought it from George Debenham’s widow.

This fitted in nicely with Charles’ awareness that the growing Grammar School needed a good playing field. George Debenham’s son Alfred Herbert, also a School Governor, helped with the levelling of the site, and 7 acres were soon presented to the school for their new Belmont Hill playing field. Many generations of local boys have benefitted from this generosity. (A small site at the north-east corner was retained to house the new Belmont Steam Laundry.)

In 1870 Charles was elected as a St Albans Councillor for three years, and in 1872 became Mayor. After that he campaigned to stop the river Ver being polluted by sewage, and in 1877 persuaded the St Albans magistrates to prosecute the Council for failing to stop the pollution. This led to the first serious moves to organise sewers and waste disposal for all parts of St Albans.

In 1875 his offer to erect a “water pillar” at the Clock Tower was accepted by the Council. There is a minor problem about this, because the elaborate drinking fountain designed by Gilbert Scott for Isabella Worley had been installed at the Clock Tower to everyone’s satisfaction in 1872, and it is not clear what else was needed.

The Woollams and the Public Library

In 1881 Charles became a founder member of the Committee which inaugurated the Public Library. He was a founder member of the County Council, a magistrate, a churchwarden and benefactor of the Abbey, trustee of most of the St Albans charities, and in 1905 was awarded the Freedom of the City. He left large bequests to the West Herts Hospital in St Albans, and to the County Museum. He was of course a member of the St Albans & Hertfordshire Architectural & Archaeological Society; Charles Ashdown represented the Society at his funeral.

Among so many other offices, Charles was a member of the St Albans Schools Board, which was responsible for the other local schools, and he determined to give their children some new recreational space. So in 1897 he purchased for £1700 the 7-acre Clay Pits meadow off Verulam Rd and presented it to the Council to make the public Victoria Playing Fields. Similarly in 1903 he purchased 3 acres of land north of Hatfield Rd, which became the Fleetville playing fields. Both these pieces of land had belonged to the Grammar School, and in buying them he was also helping their cash shortage. He also helped the School several times by lending them much-needed money, usually telling them that he did not want it back! Charles Woollam thus combined his role as a successful industrialist with a remarkable record of public service. St Albans was indeed fortunate to have men like him influencing the town’s destiny.

Abbey Silk Mill c.1900. St Albans Museums

Silk industry in decline

By the end of the century the demand for English thrown silk had declined and employment at the silk mills was down to 250. In 1906 Charles retired, and sold his mills, including the one at Redbourn, to J Maygrove Ltd, who continued to operate them, with some diversification, until 1938. (The faithful Frederick Peacock was still there in 1906 to give him and his wife retirement presents from the workers.) He moved from the Mill House to Abbey Gate House, which later became the home of the Bishops of St Albans. This marked the end of the Woollams connection with the silk business, as Charles had no children to follow in his footsteps. However Charles and Mary evidently regarded the boys of the School as their extended family, and there were frequent tea parties for them at Abbey Gate House. Mrs Biddy Hodge, daughter of Frank Walker, the resident house master at Monastery Close, also remembers being taken to visit Mrs Woollam.

Charles’ death in 1915 was greatly mourned by the City, the School and the silk workers, and he was buried at the Abbey next to Lord & Lady Grimthorpe. In his will, he expressed the hope that the open spaces which he then owned should be preserved as far as possible as public amenities. His philanthropic work was continued by his widow Mary, for example with her gift of the Lower Abbey Orchard to the Cathedral. In 1924 she presented St Albans School (the “Grammar” part of the name had been dropped) with another playing field, the Causeway, an open space which Charles had purchased many years before. Younger school members used this new facility fully, (as did also the cows from the neighbouring farm). She set up a charity fund in Redbourn, which provided allotments, and then almshouses, and she also supported the Abbey Choir financially. She died in 1925, and was buried with her husband. It was very fitting that in 2006 the Woollams’ grave was refurbished by the School and the Old Albanians, and now bears an inscribed plaque acknowledging their continuing generosity.

The Woollam name has been preserved in various ways. In 1932 the School acquired Torrington House as an additional boarding house and preparatory school, and named it Woollams. More recently the School and the Old Albanians have collaborated to establish a splendid new sports facility, named The Woollam Playing Fields, in recognition of Charles’ generosity in financing the Belmont Hill playing field a hundred years before.

There are gaps and possibly errors in this account, and more work is needed. Any information or corrections will be gratefully received.

(To contact the author click here and send an email to the Library Team)

Note: Charles Woollam’s year of birth was amended from 1833 to 1832 in October 2020 following information provided by Robert Pankhurst from parish baptism records.

Sources

Primary Sources

Debenham family records

Herts Advertiser

Kent ‘s London Trade Directories

Probate records for Charles Woollam

Secondary Sources

J. Corbett, Secret City: hidden history of St Albans, McDermott Marketing (c.1993)

N. Cossons, Industrial Archaeology, David & Charles (1975)

A. Featherstone, The Mills of Redbourn, self-published (1993)

H. Fowler, The Boundary Wall of the Monastery of St Alban, Randall (1876)

A.E. Gibbs, The Corporation Records of St Albans, Gibbs & Bamforth (1890)

W. Branch Johnson, The Industrial Archaeology of Hertfordshire, David & Charles (1970)

F. Kilvington, A Short History of St Albans School, St Albans School (1970)

R. Niblett, ‘Excavations at the Abbey Mill’, Herts Archaeology, Vol. 11, (1993), pp. 54-80

A.N. Palmer, A History of the town and parish of Wrexham, Woodall, Minshall & Thomas (1893)

J.T. Smith & M.A. North (editors), St Albans 1650-1700: a thoroughfare town and its people, Hertfordshire Publications (2003)