In 1213, the Abbot of St Albans Abbey hosted a meeting called by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Stephen Langton, and attended by many of the barons who opposed King John. In this article, based on a lecture to the Society on 6 October 2020, Dr Peter Burley, Society Vice-President and author of The Battles of St Albans, discusses why St Albans was selected for this pivotal meeting.

The genesis of the Magna Carta

The first event in the process that led to the sealing of Magna Carta at Runneymede in 1215 was a meeting of Barons and the Archbishop of Canterbury hosted by the Abbot of St Albans at the Abbey here in 1213. The question no one seemed to ask was “why St Albans?” and this paper suggests and illustrates some reasons.

The Magna Carta of 1215 is the earliest and one of the most important constitutional documents in English/British – and, indeed, world – history. It was essentially a treaty signed between King John (reigned 1199-1216) and his subjects that they would stay loyal if he agreed to rule legally and equitably. It placed tight limits on royal authority without challenging John’s right to be king.

Sealing it at Runnymede was a momentous event with repercussions down to today. Nothing like it had happened before. We stand in awe of the people who had the imagination and courage to confront their king in this way and who met in St Albans in 1213 to plan it.

Health warnings

As an historian, I do have to give two health warnings. The first is that the meeting in 1213 was only recorded in passing by one chronicler – Roger of Wendover (of St Albans Abbey) – and with almost no detail. (The other great St Albans chronicler, Mathew Paris, does not mention it, but Mathew was only 13 at the time and would not become the Abbey’s chronicler until after 1235). However, it is generally agreed by historians that the meeting in 1213 did take place and should be treated as the point at which preparations for the Magna Carta began in earnest.

The second health warning is that I will be rounding up information about St Albans from across the Middle Ages and extrapolating its relevance to 1213. Some items were only formalised in writing (e.g. in Charters) long after 1213, but I am confident that they were custom and practice much earlier and can be read back into the situation in 1213.

The controversial reign of King John

King John (National Portrait Gallery)

By 2013, King John had ruled England for fourteen years, during which he made many enemies. The timeline below suggests some of the reasons.

- 1199 – John acceded to the throne, side-lining the designated heir, Prince Arthur, the Duke of Brittany

- 1202-4 – unsuccessful war with France

- 1203 – assumed murder of Prince Arthur by John

- 1209-13 – John excommunicated by the Pope

- 1212 – Barons start to plot against John

- 1213 – Barons meet in St Albans

- 1214 – Battle of Bouvines

- 1214 – Start of the First Barons War (to 1216)

- 1215 – sealing of Magna Carta at Runneymede and temporary lull in hostilities

- 1216 – War resumes but John dies.

In fact, it is impossible to find a good side to John. Most of the many problems he faced were self-inflicted. His behaviour meant that he was widely seen as vindictive, untrustworthy and faithless. The allegations that he had his nephew Prince Arthur of Brittany murdered by 1203 overshadowed the remainder of his reign. The uncompromising stance he took against the Pope’s appointment of Stephen Langton as Archbishop of Canterbury led to the whole kingdom being placed under an Interdict between 1209 and 1213.

John’s fruitless attempts to regain the lost French territories of the Angevin Empire (see below) were expensive, contributing to a chronic lack of funds, heavy taxation and constant demands for money from his English subjects. Any hopes of restoring the Angevin Empire were dashed when John backed the wrong side at the Battle of Bouvines (see below), and it was little wonder that he was given the sobriquet “John Softsword”.

Prince Arthur, Duke of Brittany 1187 – 1203

Prince Arthur’s fate overshadowed John’s reign and was the backdrop to people’s inability to have faith in or trust him. Arthur was one of Henry II’s grandchildren and was designated by Richard I to be his heir if he died childless – which he did. However, when Richard was unexpectedly mortally wounded in 1199 Arthur was still only 12 years. To avoid a minority with the attendant risk of civil war, Richard made a deathbed change to the succession in favour of his brother John.

John evidently felt that Arthur was far too great a threat to him and had him imprisoned (in Falaise Castle in Normandy). He was never seen again and it was universally assumed by 1203 that John had ordered that he be murdered. This episode is not as famous as the Princes in the Tower, but it has striking parallels in that the two kings concerned (John and Richard III) could neither produce the living prince/s nor account for their fate, and this inability blighted the two reigns and both kings’ reputations.

The Angevin Empire

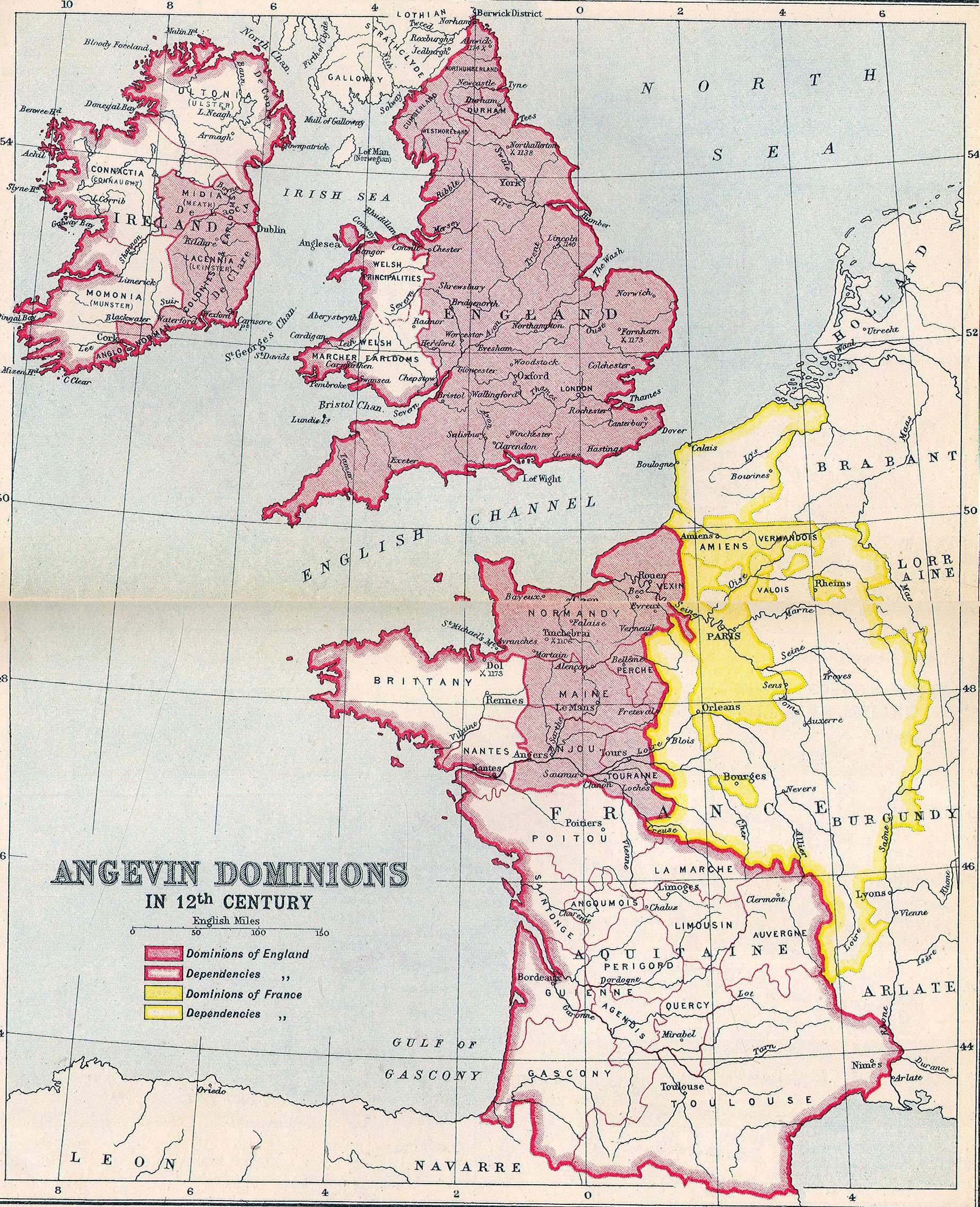

The Angevin Empire, the name of which derives from the town of Anjou where Henry II was born, stretched from Hadrian’s Wall to the Pyrenees. The most populous and prosperous half was in France. The empire began in 1152 when Henry II married Eleanor of Aquitaine. Henry brought into the empire:- England, parts of Wales and Ireland, Normandy, Brittany and some of the French provinces south of Normandy. Eleanor added the very extensive Duchy of Aquitaine, which ran down to the Pyrenees and the Mediterranean. Over half of modern France was then ruled by Henry II, Richard I and finally John, when he acceded to the throne in 1199.

The territory John inherited in 1199 is shaded pink inside the dark pink border in the map below. Ireland is included because the Angevins did lay claim to all of it even though they only controlled part of the island.

Angevin Empire in the 12th century

The French monarchy had wanted to regain these mainland territories from the start and found a weak and incompetent opponent in John. The war to regain them was over by 1204 and, of all the Angevin French territories, only the Channel Islands remained with John and his successors. John had lost half his kingdom, and it was the better half.

Battle of Bouvines 1214

The Battle of Bouvines was fought in northern France in 1214 between France and the Holy Roman Empire. In 1213 John had allied with the Holy Roman Emperor – Otto – to attack France and partition it between them. John took an army to France in 1213, but Otto failed to launch his invasion and John had to retreat home. The reverse happened in 1214 but Otto’s army then suffered a devastating defeat at Bouvines with John sitting on the side lines watching his dreams of a come-back in France evaporate. It was the most important battle for the future of England in which no English troops took part. Its outcome doomed John’s foreign policy and his credibility at home. It was the catalyst for the outbreak of the First Barons War in 1214.

Why was St Albans chosen for the Barons’ meeting?

St Albans would have had many attractions for the Barons, which I will unpack below, but in summary:-

- The invitation to meet was issued by the Abbot under the aegis of the Church,

- St Albans was geographically convenient and with good road network – so escape was also an easy option,

- The town could accommodate large numbers of visitors,

- The “Liberty of St Albans” was a palatinate not under the direct authority of the Crown,

- The Abbey was physically and (later legally) a castle, and

- The town had sophisticated defences that Matthew Paris said were second only to London’s in this part of England.

Geography

St Albans was geographically convenient and enjoyed a good road network to reach it – and to flee from it if needed. It lay on Watling Street, a day’s journey from London, and close to Ermine Street and Icknield Way.

Accommodation

St Albans was the second most popular destination for pilgrimage after Canterbury. This meant it could accommodate large numbers of visitors from all levels of society in inns, taverns and ale houses. Especially for the Barons, what became the inns could offer secure and comfortable sleeping quarters befitting their status, food, entertainment and stabling. (Inns did not acquire their legal status until Edward III’s reign, but they would have offered the same facilities in John’s reign). The shrine of St Albans and the wealth of accommodation made St Albans a more obvious and innocent place to visit than most.

The Goat, still a pub today, is one of the inns in St Albans which were probably already there in 1213, although not in the buildings we see today.

The Goat, a common lodging house in Sopwell Lane, with a ‘Beds’ notice affixed to the front, c.1905. (SAHAAS)

The Liberty of St Albans

The medieval jurisdiction of St Albans was called a “Liberty” – hence its prison being called wonderfully the “Liberty Gaol”. The more technical term was a “palatinate”, a status formally confirmed in Edward I’s reign (the most famous and longest lasting palatinate was that of Durham ruled over by a Prince Bishop until 1832). The Abbot here was the premier Abbot of England and later would have a seat in the House of Lords. The Abbot exercised the power of a sheriff inside the Liberty so what the Liberty was actually free from was direct royal interference. There were several episodes in the Middle Ages when the sheriff in Hertford tried to exercise royal authority in St Albans – and failed.

As a palatinate the Liberty was responsible for its own defence and all military and policing matters. This meant that the Abbey had to be a defensive complex as well as a place of worship and pilgrimage. In 1357 it had to buy a “Licence to Crenellate”* from Edward III. This gave it the legal status of being a castle (and authorised it to retain its defensive walls, battlements and fortified gateways), but at the cost of paying a tax to the crown.

The Abbey had possessed powerful fortifications centuries before 1357 and dating back to the Viking Wars. The Abbey also maintained its own garrison of mercenary soldiers, usually Flemings, and they saw military action mostly against the townspeople of St Albans when there were violent disputes with the Abbot. There is a record of the Abbey garrison being deployed against Stephen’s troops in the civil war between Stephen and Matilda. In 1327 the Abbey’s garrison held out for a Biblical 40 days’ siege by rioting townsfolk.

There were also half a dozen outlying “ring-fenced” parishes in the Liberty. The Liberty was co-terminus with the Hundred of Cassio(bury).

The defences of the medieval town

- Ditch and rampart surrounding the medieval town with seven openings and a hedge or palisade on top of the rampart. Gates were not installed until 50 years later on.

- River Ver closed off the town to the south and no Ditch was needed there,

- Inner defences round the Abbey Precinct,

- A central keep with two large towers (the – still surviving – Abbey Gateway and the Watergate,

- They were managed by the Abbey,

- Ditch about 10 deep and rampart about 15 feet high (from ground),

- Detailed archaeology in Keyfield and in Chime Square,

- When where they built: Started in the Viking Wars and took final form in the “Anarchy” 1135-53 – the civil war between Stephen and Matilda,

- Why: To control access to the town, enforce the curfew, charge tolls and – above all – to make wagons stop and horsemen dismount.

All this means that St Albans was laid out like a massive concentric castle with three circular layers of defences.

Why the Barons needed a secure venue

The last question here is why did the Barons go to such trouble to choose their venue? Confronting a king was not to be taken lightly. John’s enemies tended not to live long, fulfilled and happy lives – starting with Prince Arthur. For their meeting the Barons needed to feel safe both legally and physically.

This was why St Albans was so attractive. The meeting was under the aegis of the church and St Albans was outside the immediate reach of royal authority. If the king got wind of what they were doing, St Albans had strong defences against attack. The meeting was of a select few of John’s opponents – perhaps no more than a dozen – and it should have been possible to keep its true purpose secret. Also, everyone always had an excuse to be in St Albans – to visit the shrine of St Alban.