Curious facts about old St Albans

Passage through the Abbey

Passing through Waxhouse Gate between the 16th century and late 19th century, you would have found a wall blocking the way to Sumpter Yard. But you could have walked through the Abbey Church along a passage that ran between the Lady Chapel and the Shrine of St Alban.

The Cathedral passageway

The footpath was put in place at some stage following the dissolution of the Abbey in 1539, after which the Lady Chapel became a Grammar School. The rest of the Abbey was sold to the town for use as a parish church. The shrines of St Alban and St Amphibalus were broken up, and used to build a wall separating the church from the footpath. This painting (thanks to the Cathedral and Abbey Church of St Albans) shows the passage looking through towards Waxhouse Gate. It wasn’t until 1878 that a new footpath was built around the Abbey, enabling the cut-through to be closed.

Sharp right!

From the late 17th century to the early 19th century, travellers down Holywell Hill had to swerve right at the bottom of the hill, diverting along what is now Grove Road. When Sarah Churchill (neé Jennings), Duchess of Marlborough, took over Holywell House in 1684, she apparently disliked the fact that the house opened directly onto the road. She was not without influence – for many years she was a favourite of Queen Anne – so was able to acquire a section of Holywell Hill and a small area of land to the west. Grove Road was built to allow travellers to avoid her estate.

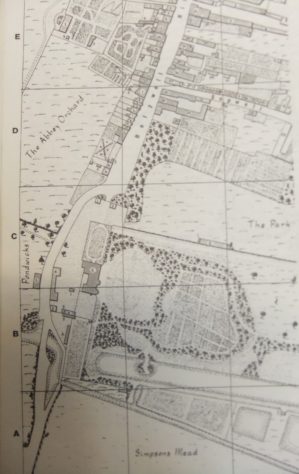

Society volunteers put together a map of St Albans c. 1820 which shows how the road was diverted. Part of the old road became a carriageway leading to the remodelled house – believed to have been designed by the architect William Talman, who later planned Chatsworth House.

Map of St Albans c1820 (SAHAAS)

Holywell House (subsequently rebuilt) and its grounds remained in the ownership of Sarah’s descendants until 1837, when the house was demolished. According to a newspaper advertisement dated 4 November 1837 in the Hertfordshire Mercury & Reformer, the Trustees of the relevant part of the Reading and Hatfield Turnpike Road were to meet on 18 November ‘to consider the expediency of a diversion of the road opposite Holywell House, so as to carry the same in a more direct line from Holywell Hill, St. Albans to St. Stephen’s’. The Trustees evidently decided it was expedient, and the road was rerouted on approximately the original axis.

The missing town cross

For hundreds of years, an Eleanor Cross stood near the Clock Tower, and served as the place for important public announcements. During the civil war that led to the execution of Charles I, Parliamentary iconoclasts vandalised and destroyed other Eleanor Crosses, including Charing Cross and one at Cheapside. It seems probable that they were responsible for damaging the cross in St Albans, after Parliamentary troops captured the town in 1643.

Eleanor Cross, Waltham Cross

In 1701, the town Corporation decided to get rid of the remaining stump, and employed contractors to remove it. In 1872 local philanthropist Mrs Isabella Worley paid for a drinking fountain to be erected on or near the site of the cross. As vehicular traffic increased it became an obstacle, and was removed in the 1920s. However, the fountain can still be found where it was re-erected behind the old prison on Victoria Street, near the railway station.

An arm and a leg

In the late summer of 1858, the Victoria Playing Fields (between Verulam Road and Folly Lane) were the scene of a cricket match played by war veterans who had lost an arm or a leg. The event was organised by local publican James Gentle, and was intended to raise money to help the veterans (and, quite likely, James Gentle).

Christ Church cricket match (with thanks to St Albans Museums + Galleries)

A close run thing

Not content with the removing the remnants of the Eleanor Cross (see above), the town authorities once contemplated demolishing the ancient Clock Tower – admittedly after it had become virtually derelict in the mid-nineteenth century.

Beth Jones alongside the finished scale model in the St Albans Museum + Gallery

Thankfully, our Society led a successful campaign to preserve the Clock Tower, and now helps to keep it open to the public.

The Clock Tower was used to toll the curfew hours, but has been put to many other purposes since then. The timbers used in the upper tower have been dated to 1401-2, suggesting that the tower was built sometime around 1405. In 2019, the Society commissioned Beth Jones to make a model to mark our Society’s 175th anniversary.

Right hand down a bit!

The route from London to the North West via St Albans used to run along the Old London Road and Sopwell Lane (home of several former coaching inns). There was then a sharp turn right up Holywell Hill, and a left turn down towards Fishpool Street – a difficult manoeuvre for horse-drawn coaches arriving in the town.

Old Toll Gate, London Road

Not until the opening in 1796 of the new toll road (the present London Road) did coaches have an easier journey. Good news for the Peahen, which won much of the passing coach trade, but bad news for the older coaching inns along the Old London Road and Holywell Hill, which lost much of their business.

The photo shows the ruinous toll house and gate where the ‘new’ London Road bifurcated from the old road (imaginatively renamed Old London Road). According to the Herts Advertiser (26 August 1871, p. 5), all the gates and toll houses along this stretch of the old turnpike road had been demolished in the previous few weeks. So, the photo was taken no later than August 1871.

What did the Romans do for us?

Europe has some fine examples of Roman aqueducts that provided fresh water to towns and cities from distant water sources. But not all aqueducts necessitated magnificent structures such as the Pont de Gard in southern France, or the Aqueduct of Segovia. There are several examples of so-called channel aqueducts in Britain. These could be open, or covered with wooden boards or flagstones. An even simpler version was the leat, a channel dug directly in the ground, and sometimes lined with clay.

Acqueduct of Segovia (Bernard Gagnon, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons)

In recent years, volunteers led by Dr Kris Lockyear have carried out an extensive geophysical survey of the site of Verulamium, and this resulted in the discovery of what appears to be a ground level water course that took advantage of gravity to deliver water through the west of the municipium. This may have been used to provide richer households with their own supply of running water, feed public water fountains and flush drains and latrines.

The other St Albans

St Albans, Bay D’Espoir, Newfoundland, Canada

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, many emigrants sailed from Britain to new lands, taking a few possessions and the memories of where they had come from.

Often the new towns and villages they established were badged with the names of the places they remembered from home. As a result, there are at least six other St Albans scattered around the world. You can read more here about these other St Albans.