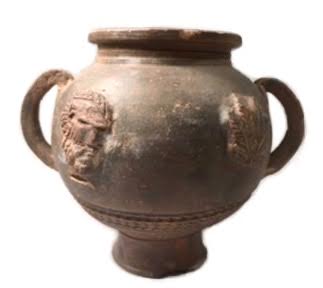

The significance of an unusual black terra-cotta jar found in Verulamium, which appears to feature images of the Greek Dionysos or Roman Bacchus or, possibly, the Celt Cernunnos

Fig. 1: Black Samian Jar, fine ware drinking vessel

used by the upper class for serving wine,

c.150-160 AD (© St Albans Museums)

In the 1950s, this complete Terra Sigillata terra-cotta jar was excavated by Sheppard Frere at Verulamium (Insula XIV, Room 55). (Fig. 1.) in a building destroyed by fire in the early Antonine period, (c.150–160 AD). This room was located in the final rebuilding of the half-timbered shops and was the terminal room of its suite which served as a store-room. The jar is of Gaulish manufacture measuring 15cm high and 10cm width. There are two face-masks, one of a bearded male possibly with hair and the other of a female with long hair, as well as an ivy leaf running around its shoulder. There are pattern-impressed, roulette decorations running around/towards the base (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Pattern-impressed roulette

decorations (© St Albans Museums)

The jar has been classified as black Samian type ‘Dechelette 74’ because of its form, unusual colour and applied motifs. Its black colour is because, unlike common red ware, it was fired under reducing conditions. Its motifs, unlike the common impressed or stamped types, are applied molds. The jar is a fine ware drinking vessel used by the upper class to serve wine.

Dionysos and Bacchus …

The applied motifs suggest the Greek Dionysos cult of Dionysia. This cult was later assimilated by the Roman world into the Bacchus cult (‘Bacchanalia’). We can recognise the followers of Dionysos and Bacchus on this jar in two ways. Firstly, the followers are represented by a Seilenos’s head (Fig. 3) and a Maenades’s head. These motifs may suggest the occurrence of the cult and eventually the adoption of new traditions by the local elite, to celebrate the god by intoxication and ecstasy.

Fig. 3: Probable Seilenos motif (© St Albans Museums)

Seilenoi were anthropomorphic creatures, part man and part beast; they are more ancient than satyrs. In art, Seilenoi are mostly represented as bearded and balding and with a horse tail. The Maenads were the most important female followers in the thiasos, (the gods’ retinue), and were inspired by Dionysos into a state of ecstatic dance suggestive of possession of the god. Secondly, the ivy leaf may suggest the plant wrapped around a long stick, a thyrsos, which was used by the Maenads to hit the ground to get honey and milk. Alternatively, it may be one of the attributes of Dionysos found wrapped around his wreath. By the mid-2nd century AD the Roman Bacchus cult had become popular in the Empire and, as other mystic cults, enough was known by a wide public for its attributions to have an apotropaic function (i.e. the power to avert evil influences). During cult events wine was served in fine decorated vessels which would have recalled the event of the Bacchanalian festival.

… and possibly Cernunnos

On the other hand, these applied motifs could also suggest a classical syncretism with the Celtic god Cernunnos by representing him in the guise and attributes of Greco-Roman divinities. Cernunnos shares with Dionysus and Bacchus the primary interpretation of fertility of nature and fecundity of men and animals. He also shares the horned serpent. Dionysos-Zagrèus was a cult which celebrated mankind as a life force which regenerates itself cyclically (zoé) and is not bound to the time limits of human conditions (bios).

The Dionysos cult was centered on the Thracian region. Here the Celts living on the shore of the Black Sea came in close contact with the Greeks. It is possible that the (Celtic) Cernunnos cult by its reverence of the serpent and of the snake’s egg (ovum anguinum, as Pliny refers to it), among the inhabitants of Gaul may be an independent development. However, there is at least some possibility that their ram-headed serpent has connections with Greek mythology which in time was absorbed by the Romans. And found its way to Verulamium.

There’s a fully-referenced version of this note in the Society’s Library. With thanks to Simon West for his comments on an early draft.